No evidence for farmers’ claim that Sea Eagles predated Shetland ponies

Five foals vanished from a South Uist farm amid claims of eagle predation – but official nest checks have found no evidence, leaving the case unresolved

The farmer’s claim

Donald John Cameron, who runs Long Island Retreats on South Uist, reported the sudden disappearance of five Shetland pony foals between May and July 2025. Convinced that White-tailed Eagles Haliaeetus albicilla were responsible, he described the losses as both devastating for his family and damaging for the agritourism business that relies on the ponies to attract visitors.

“They’re not just livestock, they’re pets,” Cameron told reporters. “My four-year-old names every foal, and it’s heartbreaking when they vanish.” He pointed out that with no foxes or pine martens on the islands, and mares failing to remain with the bodies as they normally would, predation by sea eagles seemed the only explanation.

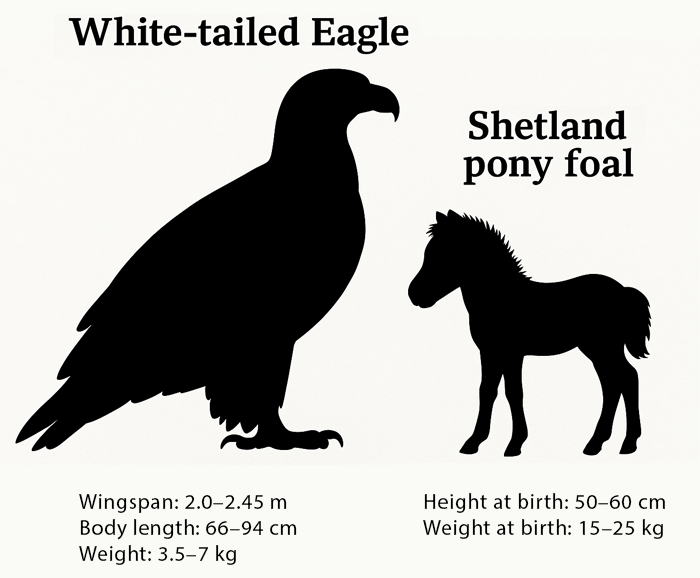

Weighing little more than a four- to five-week-old lamb, the foals were small enough, he argued, to be vulnerable to the island’s growing eagle population. Reports of the birds circling fields close to the grazing areas fuelled his suspicions.

Official investigation

In response, NatureScot, Scotland’s government nature agency, launched an inquiry under its Sea Eagle Management Scheme. Officers examined prey remains in the two closest White-tailed Eagle nests to Cameron’s croft, seeking physical evidence of the missing foals.

Analysis revealed a diet dominated by seabirds such as Fulmars, Eiders and Puffins, along with rabbits and Greylag Geese. Crucially, no bones or hair consistent with Shetland ponies were recovered, nor were lamb remains present. NatureScot concluded there was no evidence linking the eagles to the foal disappearances.

“While we understand the farmer’s concerns, our investigation has not found any indication that sea eagles were involved in these losses,” a spokesperson said. “We will continue to offer advice and support.”

Conservation and conflict

The episode underscores the continuing tensions between conservation success and rural livelihoods. White-tailed Eagles, once extinct in Britain, were reintroduced in the 1970s and now number several hundred pairs across Scotland, including the Outer Hebrides. While celebrated as a flagship species, they remain controversial among crofters and farmers who fear predation on lambs and other young stock.

Scotland’s Sea Eagle Management Scheme was established to ease such conflicts, offering practical measures and limited financial assistance. Yet disputes over evidence often leave both sides frustrated – farmers convinced of losses, agencies constrained by the need for proof before compensation is offered.

An unresolved mystery

Despite the nest checks, the fate of Cameron’s five missing foals remains unknown. No carcasses have been recovered, and no alternative explanation has been confirmed. For the farmer, the absence of evidence is not enough to dispel his belief that the eagles are to blame.

“We’re left with no answers,” he said. “The foals are gone, and it’s our family and our visitors who feel the loss.”

For now, the South Uist case illustrates the difficulty of proving or disproving predation claims in remote landscapes. Without hard evidence, the mystery of the vanished foals lingers – a story caught between anecdote, science and the uneasy coexistence of people and raptors.

September 2025

Share this story