Cats Kill an Estimated 60 Million Birds in Canada Each Year

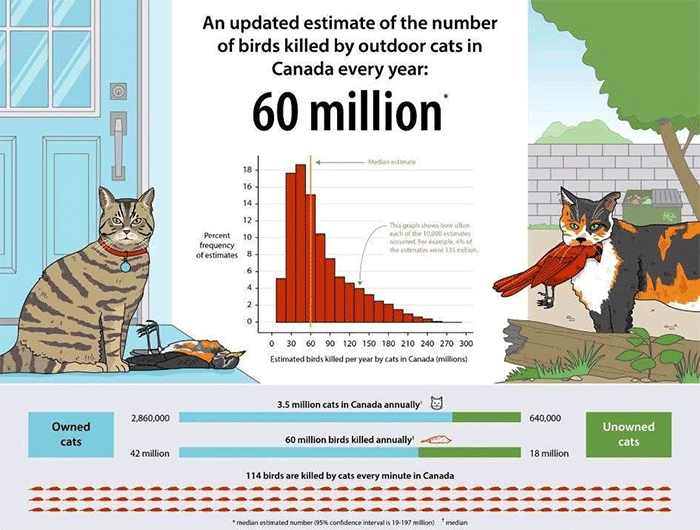

New national study revises the estimated toll from outdoor cats to around 60 million birds annually – a sharp drop from 2013 figures, but still a major conservation concern.

Updated estimates paint a complex picture

A new study in Avian Conservation and Ecology has sharply revised down the estimated number of birds killed by cats in Canada – from as many as 348 million a decade ago to a current range of 19–197 million, with a median estimate of 60 million birds lost each year. Though the figure is 71% lower than the 2013 estimate, the authors emphasise that outdoor cats remain one of the country’s leading human-related causes of bird mortality.

Researchers led by Jonathan Chu at the University of Guelph re-evaluated national figures using more accurate field-based cat population surveys and updated predation studies. Earlier estimates had relied heavily on owner surveys and shelter intake data. “We now have a better idea of how many cats are actually outdoors and how often they hunt,” said Chu. “Our findings show fewer outdoor cats than once assumed – but the threat to birds is still serious.”

Field data over guesswork

The updated analysis drew on recent field studies using walking transects and trail cameras to estimate outdoor cat populations in five Canadian localities – from Vancouver to Gatineau. These were then scaled up to give national estimates. The team also reviewed more than 50 international studies on cat predation, including camera-based research that records hunting directly rather than relying on owners’ reports of prey brought home.

The results suggest that roughly 3.5 million cats spend time outdoors in Canada. Urban owned cats account for most of the predation, killing about 27 million birds a year. Rural cats kill around 8 million, while unowned or feral cats – though fewer in number – are responsible for an estimated 18 million kills annually.

Why the big drop?

The researchers attribute most of the 71% reduction in national mortality estimates to improved population data, not to any real decline in cat numbers or predation rates. Earlier studies appear to have overestimated how many cats were roaming outdoors. Newer evidence indicates that fewer pet cats are allowed outside – around 30–60% today – as more owners choose to keep them indoors for welfare and wildlife reasons.

Predation rate estimates have also been refined. Modern camera studies show that many earlier surveys exaggerated kill numbers by assuming that every prey item brought home represented a typical catch. “Cats don’t always bring birds back to their owners,” said Chu. “Video data helps correct those biases, giving us more realistic, if still worrying, numbers.”

Remaining uncertainties and next steps

Despite improved methods, the authors caution that major knowledge gaps persist. Only one Canadian study has directly measured the number of unowned cats, and none has quantified how many birds cats kill within Canada itself. Much of the data still comes from temperate regions such as the USA, UK, and Australia.

Rural areas remain particularly under-studied, yet cats there may have greater impact due to higher densities of outdoor animals and abundant wildlife prey. The team calls for more systematic fieldwork, including mark-recapture and camera studies, to distinguish between owned, stray, and feral cats and to understand how behaviour and climate affect hunting rates.

A continuing conservation issue

Although the revised estimate is lower, the study reinforces that outdoor cats are still a major source of bird mortality – killing tens of millions of individuals annually. In a country that has already lost an estimated three billion birds since 1970, this remains a significant pressure on wildlife populations.

Lead author Chu and colleagues stress that improved data should guide, not diminish, conservation action. Measures such as keeping cats indoors, supporting trap-neuter-return programmes, and local education campaigns remain vital. “This isn’t about blaming pet owners,” said Chu. “It’s about understanding the scale of the issue and finding humane, effective ways to protect both cats and birds.”

October 2025

Read the full paper here

Get Breaking Birdnews First

Get all the latest breaking bird news as it happens, download BirdAlertPRO for a 30-day free trial. No payment details required and you will get access exclusive first-time subscriber offers.

Share this story