White-naped Cranes use two clearly separate migration routes across east Asia

Satellite tracking shows eastern and western breeding populations follow different flyways, use different stopover sites and rarely mix

For decades, ornithologists have known that White-naped Cranes Antigone vipio breeding in different parts of East Asia winter in different places. What has remained unclear is just how sharply those populations are divided in their migration routes - and whether they move in fundamentally different ways. A major new satellite-tracking study now provides the clearest answer yet.

By following the movements of 87 individual cranes over nearly a decade, researchers have revealed a distinct migratory divide separating eastern and western breeding populations, with each group adopting a contrasting migration strategy shaped by geography, habitat availability and ecological barriers.

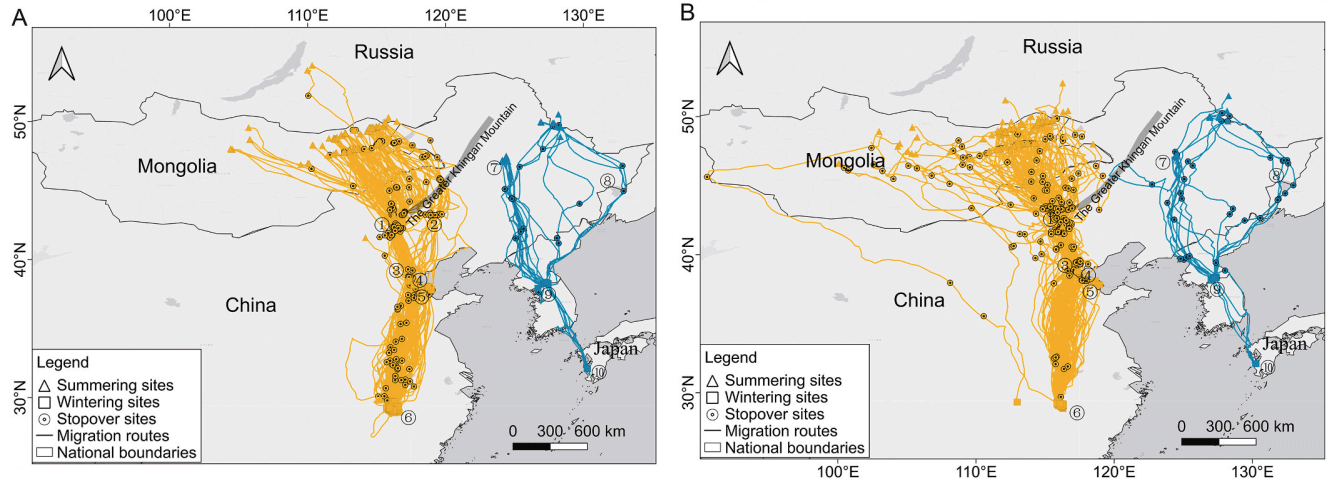

Two populations, two flyways

White-naped Cranes breed across a wide swathe of north-east Asia, but the species is split into two broadly separate populations. Birds from the western population breed mainly in Mongolia and adjacent regions, while those from the eastern population breed in north-east China, including the Songnen Plain and areas along the Sino-Russian border.

Satellite tracking shows that these two populations follow entirely different migration routes. Western birds migrate south through Inner Mongolia and northern China, wintering in areas such as the Yellow River Delta, Tianjin, Cangzhou and Poyang Lake. Eastern birds, by contrast, move east and south-east, staging on the Korean Peninsula before wintering either there or in southern Japan.

The divide between the two flyways is striking. The Greater Khingan Mountains and the Bohai-Yellow Sea region form a clear ecological barrier, with almost no overlap in routes. Despite years of tracking, there is virtually no evidence of regular exchange between the two populations.

Long and slow versus short and fast

Beyond geography, the study reveals that the two populations migrate in fundamentally different ways. Western birds undertake much longer migrations overall, travelling greater distances at slower speeds and relying on a larger number of stopover sites. Their journeys are extended, with long stopovers used to rest and refuel, particularly north of the Yellow River Delta.

Eastern birds follow a contrasting strategy. Their migrations are shorter, faster and more direct, with fewer stopovers and less time spent on passage. Some birds moving between the Songnen Plain and the Korean Peninsula migrate almost non-stop, while those wintering in Japan typically make just one prolonged stop on the peninsula.

These differences are consistent across both autumn and spring migration, underlining that the two populations are not simply taking different routes, but have adopted distinct migration strategies.

The importance of key stopover sites

The study highlights the outsized importance of a small number of critical staging areas. For eastern birds, the Demilitarised Zone on the Korean Peninsula emerges as especially important. All tracked individuals used this area, often for extended periods, with some remaining there throughout the winter.

For western birds, a chain of sites across northern China plays a similar role. Areas such as Duolun, Chifeng, Tianjin and the Yellow River Delta function as both stopover and wintering sites, underlining their importance for the species’ survival.

The cranes’ strong tendency to avoid long over-water crossings also makes coastal and near-coastal wetlands particularly valuable, concentrating large numbers of birds into relatively small areas.

Climate change and shifting wintering ranges

The findings also hint at longer-term changes underway. Western White-naped Cranes were once thought to winter almost exclusively in the Yangtze River basin, but increasing numbers are now wintering further north. Shorter migration distances may reflect warming winters and changing habitat conditions, a pattern already seen in other large waterbirds.

If these trends continue, sites such as the Yellow River Delta are likely to grow even more important in future, increasing the conservation stakes in regions already under heavy pressure from development.

Why migratory divides matter

Migratory divides are more than lines on a map. By separating populations in space and time, they can shape survival, exposure to threats and even long-term evolution. Although genetic studies suggest only limited differentiation between eastern and western White-naped Cranes, the near-complete separation of their migration routes raises important questions about how these populations will respond to future environmental change.

The study also underlines a key conservation message: protecting breeding sites alone is not enough. Each population depends on a distinct network of stopover and wintering habitats, meaning conservation measures must be tailored to the specific flyways each group uses.

As satellite tracking continues to transform our understanding of bird migration, White-naped Cranes offer a clear example of how a single species can live very different migratory lives - divided not by distance alone, but by landscape, strategy and history.

January 2026

Get Breaking Birdnews First

Get all the latest breaking bird news as it happens, download BirdAlertPRO for a 30-day free trial. No payment details required and get exclusive first-time subscriber offers.

Share this story