Tracking reveals precise blueprint for Red-backed Shrike migration

Researchers show that Red-backed Shrikes organise their 20,000-kilometre journeys into predictable stages, suggesting migration is governed by an inherited travel plan refined by environmental cues.

A long-standing mystery in bird migration

For more than a century, studies of caged songbirds have shown that migrants possess an internal circannual programme that triggers migratory restlessness in spring and autumn. This has long been taken as evidence that birds are genetically primed to migrate, but it has remained unclear how closely this internal programme translates into the actual pattern of flights made by birds travelling freely across continents.

New research using miniature multisensor data loggers now provides the clearest answer yet. By tracking the full annual flight activity of free-flying Red-backed Shrikes Lanius collurio, scientists have discovered that migration is not a diffuse series of opportunistic flights, but a tightly organised journey made up of distinct, repeatable flight segments.

Tracking a 20,000-kilometre journey

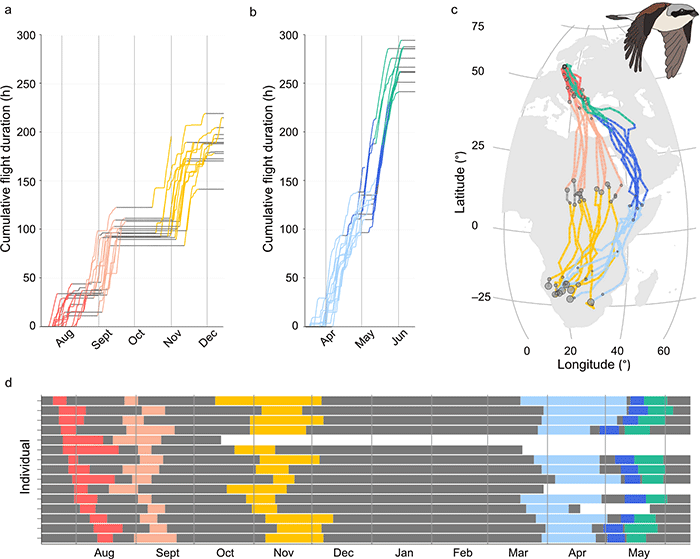

The study followed 15 adult Red-backed Shrikes breeding in Denmark, each equipped with a lightweight logger that recorded activity every five minutes throughout the year. These birds undertake an extraordinary loop migration of around 20,000 km, travelling between Scandinavia and southern Africa.

Rather than spreading their migratory flights evenly across the autumn and spring seasons, all individuals showed the same striking pattern. Their nocturnal flights were clustered into six clearly defined segments – three in autumn and three in spring – separated by long stopovers or marked shifts in flight direction.

Six segments, shared by every bird

In autumn, the shrikes first moved from Scandinavia into south-eastern Europe, then crossed the Mediterranean and Sahara into the Sahel, before a final long segment carried them deep into southern Africa. Spring migration followed a different structure, beginning with a rapid trans-African crossing, followed by a near-continuous sequence of flights across the Arabian Peninsula and Europe back to the breeding grounds.

Crucially, these segments were present in every individual and showed remarkably low variation. Total flight time, number of flights, and the duration of each segment were highly consistent between birds, despite differences in weather, timing and year. In some cases, variation between individuals was less than 10%.

This figure shows how Red-backed Shrikes complete their migrations between Denmark and southern Africa in a series of distinct travel stages. (a) and (b) show how flight time accumulates during autumn and spring, with each line representing one bird. Stepped rises mark nights spent flying, while flat sections show stopovers. (c) maps the main migration routes of tracked birds, with grey circles marking longer stopovers. (d) shows how each bird’s journey is divided into separate flight phases (coloured) and resting periods (grey), highlighting the highly structured nature of migration.

Not what cage studies predicted

This structured pattern contrasts sharply with expectations based on experiments with caged birds. In captivity, migratory restlessness tends to occur on most nights throughout the migration period, suggesting a broad readiness to fly whenever conditions allow.

In the wild, however, the shrikes behaved very differently. Long periods of complete inactivity were followed by bursts of intense migratory flight, with weeks or even months separating major segments. The birds’ longest and most demanding flights often occurred late in the season, rather than at the peak of restlessness predicted from cage studies.

A detailed internal travel plan

The findings suggest that birds possess a far more detailed internal “travel plan” than previously assumed. Rather than simply controlling the overall timing and distance of migration, the internal programme appears to regulate when major flight phases should occur, how long they should last, and when prolonged stopovers are required.

The authors propose that this internal plan likely interacts with external cues such as day length, geography and geomagnetic signals. These cues may act as signposts, allowing the bird to progress from one segment to the next at the appropriate point along its journey.

Rethinking how migration is controlled

By revealing a hidden structure in the annual flight activity of a migratory songbird, this study challenges the long-held assumption that migration is largely shaped on the fly by weather and fuel availability. Instead, it points to a migration system that is both genetically programmed and dynamically adjusted through environmental feedback.

As tracking technology continues to improve, similar patterns may emerge in other long-distance migrants. What is already clear is that bird migration is not just a matter of flying when conditions are right, but of following an inherited itinerary refined by millions of years of evolution.

December 2025

Get Breaking Birdnews First

Get all the latest breaking bird news as it happens, download BirdAlertPRO for a 30-day free trial. No payment details required and get exclusive first-time subscriber offers.

Share this story