No evidence that ‘black-eye’ symptom affects Gannets after bird flu

A detailed post-outbreak study finds no impact of the black-eye symptom on foraging behaviour, nest attendance or breeding output

The devastating outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAIV) that swept through seabird colonies in 2022 caused unprecedented losses among Northern Gannets. At some colonies, more than half of all breeding adults were lost in a single season. A new long-term study from Brittany now offers a more nuanced picture of what followed – revealing unexpected resilience among survivors, alongside stark warnings for the future.

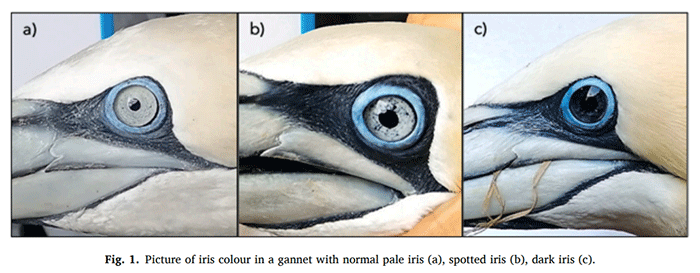

The research focused on the Northern Gannet colony on Rouzic, off the north coast of Brittany, the southernmost breeding site in Europe. One year after the outbreak, the colony had declined by 38%, and more than one in five surviving breeders showed a striking physical legacy of infection – darkened or spotted irises, dubbed the ‘black-eye’ symptom.

Zombie birds behaving normally

Despite their altered appearance, these so-called ‘zombie’ gannets were found to forage in exactly the same way as birds with normal pale eyes. GPS tracking during the 2023 breeding season showed no significant differences in trip length, distance travelled, foraging areas used, or time spent attending the nest.

The findings are important because the black-eye symptom has been linked to previous exposure to HPAIV. Until now, it was unclear whether such birds suffered lasting impairment – particularly to vision, which could affect hunting efficiency at sea. This study finds no evidence of that.

In short, birds that survived infection and returned to breed were functioning normally, feeding successfully and raising young at comparable rates to unaffected individuals.

Fewer birds, easier feeding

While individual behaviour remained unchanged, the population-level effects of the outbreak were striking. With far fewer birds competing for food around the colony, foraging trips in 2022 and 2023 were significantly shorter and closer to home than in earlier years.

This aligns closely with Ashmole’s halo hypothesis, which predicts that large seabird colonies deplete food near breeding sites, forcing adults to travel further. When colony size suddenly collapses, competition eases – and the remaining birds benefit.

Breeding success reflected this shift. After an almost complete reproductive failure in 2022, productivity rebounded sharply in 2023, rising above the long-term average for the colony. In effect, fewer birds were able to raise more chicks, more efficiently.

Sex differences persist

The study also confirmed a long-known pattern in gannets: females undertook longer and more distant foraging trips than males. However, both sexes continued to use the same feeding areas, suggesting differences in energetic demand rather than spatial segregation.

These sex-based differences remained consistent regardless of iris colour, further reinforcing the conclusion that previous infection did not alter foraging capability.

Resilience has limits

While the short-term picture may appear cautiously positive, the authors stress that this resilience should not be mistaken for security. Northern Gannets, like many seabirds, are already under pressure from climate change, prey shifts, fisheries bycatch and competition for food.

Repeated disease outbreaks, or a series of poor years driven by environmental change, could push depleted colonies past a tipping point where reduced numbers and productivity are no longer sufficient to sustain recovery.

The black-eye symptom may yet prove useful as a visible marker of past infection, allowing researchers to track survival and immunity in future outbreaks. But the wider message is clear: one catastrophic event can be absorbed, but cumulative pressures may prove far harder to withstand.

As avian influenza becomes an increasingly persistent global threat, long-term monitoring – combining tracking, demography and disease surveillance – will be critical in understanding which seabird populations can recover, and which may quietly slip towards local extinction.

January 2026

Get Breaking Birdnews First

Get all the latest breaking bird news as it happens, download BirdAlertPRO for a 30-day free trial. No payment details required and get exclusive first-time subscriber offers.

Share this story