Nape Colour in Great Shearwaters Found to Reflect Sex, Not Age

Study overturns long-held assumptions about age-related plumage in Great Shearwaters, revealing a subtle but consistent link to sex instead

Testing an ageing tool at sea

Ageing seabirds at sea has long posed a challenge to researchers, particularly in petrels, where external cues are limited. A new study led by Ewan D. Wakefield and colleagues investigates whether nape colour - the pale or dark feathers on the back of the neck - can distinguish young from adult Great Shearwaters (Ardenna gravis). Contrary to previous field guides and expert suggestions, the researchers found no consistent age-related difference. Instead, nape colour correlated more reliably with sex, especially in wintering individuals.

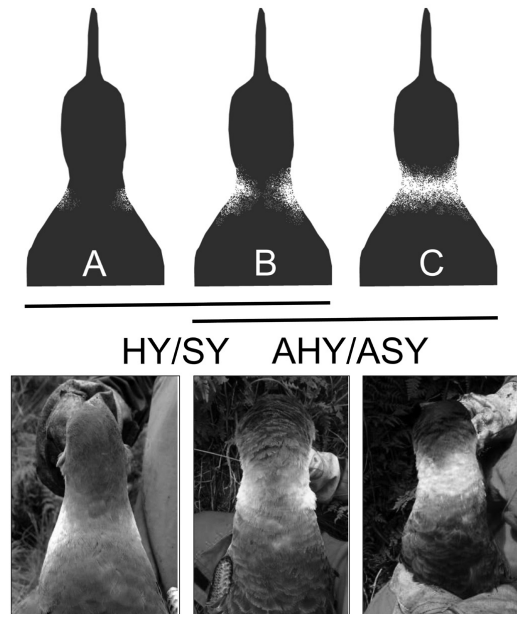

The findings, published in Marine Ornithology, involved necropsy and photographic analysis of 328 individuals, including birds bycaught in Massachusetts Bay and from breeding colonies on Gough and Inaccessible islands. Using blind scoring of plumage, the team tested whether birds with light napes were more likely to be adults, as previously suggested. But while darker napes were somewhat more common in fledglings, the pattern was weak and statistically insignificant.

Sex matters more than age

While nape colour proved an unreliable indicator of age - with a classification accuracy of just 52% - it did show a statistically significant correlation with sex. In particular, mature females in Massachusetts Bay were more likely to exhibit light nape plumage than males. This pattern was not observed at Gough Island, raising questions about regional or seasonal influences.

The authors suggest this difference may hint at a sexually selected function, possibly related to mate choice or display. Unlike many birds, Procellariiformes are not known for sexually dimorphic plumage. However, the presence of subtle, sexually differentiated traits - especially those visible in dim light or highlighted during behaviours like allopreening - could play an important role during courtship. Light feather patches, though structurally white rather than pigmented, may still signal individual quality through their brightness and wear resistance.

Could feather wear be misleading?

The study also explored whether feather wear might explain nape lightening over time. As shearwater body feathers are white with brown tips, abrasion could increase the apparent paleness of certain areas, such as the nape. Juveniles in their first year typically retain fresher plumage into the northern summer, while adults begin their post-breeding moult later. These seasonal dynamics may have contributed to the perception that older birds have lighter necks - a view that this study now casts into doubt.

Interestingly, while females bycaught off Massachusetts had more pale napes, this trend was not echoed among birds sampled nearer their breeding colonies. Nor did researchers find supporting evidence that females and males differed in moult timing - a potential explanation drawn from studies of albatrosses but not yet supported in shearwaters.

A new direction for seabird field ID?

Ultimately, the researchers conclude that nape colour is too variable to reliably determine age in Great Shearwaters, but may hold promise for studying sex-related variation and behaviour. They advocate for further work within breeding colonies to explore how plumage variation might influence mate selection and reproductive success. Such research could also consider visual cues outside the human-visible spectrum, as some plumage features may be more discernible to the birds themselves than to observers.

The work highlights the value of integrating field observation, photography, and anatomical analysis to test long-standing assumptions in seabird biology. While hopes for a simple ageing shortcut were dashed, a new window has opened onto the complex and potentially sexually selected world of shearwater plumage.

June 2025

Share this story