Male-Plumaged Female Hummingbird Provides Parental Care in Costa Rica

Observation of a Veraguan Mango nesting in an urban setting suggests a possible female-limited plumage polymorphism

An unusual discovery on a roadside powerline

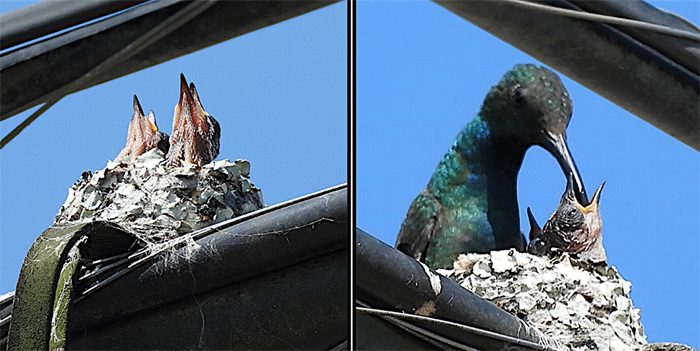

In February 2025, researchers documented a striking and unusual case in Palmar Norte, southern Costa Rica: a Veraguan Mango (Anthracothorax veraguensis) with the shimmering blue throat and breast typical of males incubating eggs and later feeding two nestlings. The nest was built just 5.5 metres above the ground, attached to a roadside powerline near a busy supermarket, amidst the noise of constant vehicle traffic. Despite the urban setting, the bird carried out parental care in full view of passing lorries and motorbikes.

Identifying a female in male dress

Closer inspection revealed details pointing to the bird being a female despite its male-like plumage. The hummingbird’s tail feathers carried white tips, a trait found in adult females but absent in males. Combined with the clear evidence of nesting and chick-feeding – roles almost exclusively undertaken by females in hummingbirds – the researchers concluded that this was a case of a female Veraguan Mango retaining male-like plumage into adulthood.

Rare but not unheard of

Roughly a quarter of hummingbird species are known to produce occasional females with male-like feathers, but the phenomenon is rarely seen in the wild. Even fewer cases exist where such birds have been observed engaging in parental care. Previous reports have come from species such as the White-necked Jacobin, Green-breasted Mango, and Black-throated Mango. This observation makes the Veraguan Mango only the third species in the genus Anthracothorax to show such behaviour.

Possible explanations for male-like plumage

The authors suggest several hypotheses for why a female would retain male-like plumage. One possibility is an age-related plumage pattern, where some females fail to transition fully to typical female plumage after their juvenile stage. Another explanation is social selection: appearing male may reduce harassment by other hummingbirds at feeders or territorial flowers, allowing female-plumaged birds to forage or raise young with fewer disturbances. Ecological pressures could also play a role – in urban environments where predators are fewer, the conspicuous male-like colours may not pose the same risks as in natural forest settings.

Urban implications

The nest’s location in a noisy urban environment raises further questions. The researchers note that female mangoes with male-like plumage may find advantages in such modified habitats, where reduced competition and predator pressure could balance out the risks of conspicuousness. However, urban settings also bring dangers, from domestic cats to collisions with windows and vehicles. The survival of this nest shows both the adaptability of hummingbirds and the potential influence of human-modified landscapes on rare plumage traits.

A window into hidden diversity

While a single observation cannot confirm whether male-like plumage in female Veraguan Mangoes represents a stable polymorphism or a rare anomaly, the study adds valuable data to hummingbird natural history. As the authors note, the case “opens the possibility of a female-limited polymorphism” in this little-known species. Future work will be needed to establish how common this condition is – and what it might reveal about the pressures shaping hummingbird plumage evolution in both natural and urban environments.

September 2025

Share this story