Century of Change: Morphological Shifts in Colombia’s Rainforest Birds

New study reveals complex and species-specific changes in body size and shape among tropical birds over 109 years, with implications for climate adaptation

Climate change leaves its mark on bird morphology

Using over a century of data from museum specimens, researchers have uncovered notable morphological changes in tropical birds inhabiting the lowland rainforests of Barbacoas, Colombia. By comparing specimens collected in 1912 and 2021, the study revealed a nuanced picture: hummingbirds showed consistent decreases in body size, while non-hummingbirds displayed a mix of size increases and decreases across species.

The findings, published in *Evolutionary Ecology*, are part of the Colombia Resurvey Project, which revisited sites originally sampled by the American Museum of Natural History over 100 years ago. The Barbacoas region, which has experienced little forest loss and remains largely pristine, offers a rare opportunity to assess climate-driven changes without major confounding habitat transformation.

Warming temperatures in a stable forest landscape

Mean annual temperature in the Barbacoas region has risen by approximately 0.88°C since 1950, although annual precipitation has not changed significantly. This warming provides a plausible environmental driver for observed morphological shifts, including changes in body size and limb proportions that align with established ecological theories like Bergmann’s and Allen’s rules.

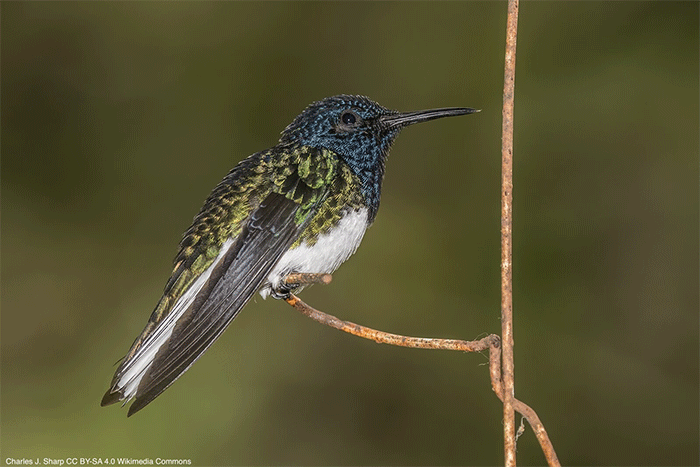

Despite the stable landscape, birds exhibited notable structural changes. Hummingbirds such as the White-necked Jacobin (Florisuga mellivora) showed strong evidence of shrinking body size, while species like the Tawny-faced Gnatwren (Microbates cinereiventris) and Pacific Antwren (Myrmotherula pacifica) among non-hummingbirds grew larger over time.

Wing and tail reshaping could reflect forest structure

Across the 23 species analysed, wing lengths generally decreased, while tail lengths increased in over 60% of species, by an average of 4.4%. This shift could reflect subtle changes in forest structure, perhaps from increased secondary growth or altered understory density, requiring enhanced manoeuvrability and flight control.

These changes might also reflect sexual selection, particularly if species use their tails in display. However, the dominant interpretation relates to changes in functional adaptation for movement within increasingly complex vegetation.

Beak dimensions increasing in parallel with warming

In addition to shifts in size and proportions, the study found strong evidence of increased maxilla (upper beak) depth in 10 of 23 species. This aligns with Allen’s rule, which predicts larger appendages in warmer climates to aid heat dissipation. Beaks, more so than tarsi, appear responsive to warming, likely due to their role in thermoregulation and feeding.

Interestingly, the increase in maxilla area - while evident - was only significant in one species, suggesting that detailed measurement of such subtle traits remains challenging, particularly in smaller birds.

Contrasting trends reflect complexity of climate responsesThe authors emphasise the complexity and species-specific nature of the morphological responses observed. While climate change is a likely driver, other indirect factors - such as changing food availability, interspecies interactions, or microhabitat shifts - may be influencing morphology. Notably, species from more open habitats showed stronger evidence of body size reduction, possibly due to greater exposure to rising temperatures.

The results challenge the notion of universal responses to climate change, showing that even in largely undisturbed tropical environments, birds adapt in diverse ways. Small-bodied species, in particular, appeared more morphologically responsive - a finding echoed in other tropical studies.

Why this study matters

Long-term datasets from tropical regions are rare, making this century-spanning study especially valuable. The subtle but measurable changes in body shape and size serve as indicators of broader ecological shifts and highlight the importance of continued monitoring. The study calls for further investigation into the mechanisms behind these changes, combining ecological, behavioural, and physiological research to fully understand how tropical birds - and biodiversity more generally - are coping with a warming world.

July 2025

Share this story