That was the spring that was...

A look back at the often remarkable birding moments of April through June 2015

”Insane in the membrane - Insane in the brain!…”

The dark, intense, trip-hop Latino-infused doper groove of Cypress Hill’s early 1990’s fug-beats became an ever more constant refrain in the head as the past three months of 2015 trundled, sometimes breathlessly on their merry way - at times it felt like it was all a little on the slow side, but on other occasions many folk really didn’t know quite which way to turn…

Spring really can be the most curious and frustrating of all four seasons - lasting anywhere from late March through to the latter end of June (weather dependent of course) - and the early days of Spring 2015 were just that - a little curious and certainly frustrating as the winter dormancy seemed to take an eternity to cast off the cold clouds of the third month of the year and edge towards the exciting days, weeks and months of the spring that lay ahead.

Those unholy grey shrouds of March glumness ensured a rather torpid start to spring, but quickly birds began to whirr and fizz like a Catherine Wheel of rare as the weeks of April rolled in to May and they, in turn, bundled their way along towards June.

In reality, it wasn’t much of a wait for spring - it just felt like it was taking some time to get here (especially - inevitably - on the east coast) - but the first signs of encouragement didn’t take long to emerge; indeed by the time we reached April, there’d already been a rather lovely singing male Desert Wheatear on Scilly, spending his time on the rocks of St. Agnes from March 21st through to 26th - becoming the seventh British record for the month in all - and a frequently obliging nice’n’early Alpine Swift near Gatwick Airport, in West Sussex, from March 28th.

The early days of April saw further glimmers of hope - there was the brief (< than 60 seconds) single observer Crag Martin at East Dene, Bonchurch on the Isle of Wight during the late afternoon of 7th while more traditional very early spring overshoots, in the guise of Black-winged Stilt and a trio of Night Herons, found routes through to Dorset and Scilly respectively.

By the time we turned the corner in to the second week of April, the weather gave us many a clear blue sky and pleasing temperatures - conditions that enabled a huge Hoopoe shaped corridor to open up - figures for the period between April 8th-14th managing to find their way to, give or take one or two here and there, bang on the 100 mark - that really was quite some influx.

Birds were strewn across the southwest of England, the west coast of Wales along with Irish headlands too - and in Waterford, Hoopoes were joined by a Western Subalpine Warbler at Brownstown Head (on 11th) while Cork managed two more classic early April overshoots, a Red-rumped Swallow making it to Mizen Head on 9th, with a male Woodchat Shrike dropping briefly on to Cape Clear Island on 13th.

The optimum overshoot conditions for the southwest of England and southern Ireland were hollering - loud and proud - for something out of the box marked “high quality” and as the weather continued to become better and better it was the classic case of “when” and not “if” there’d be a grand bird discovered.

Sure enough, come April 10th, the ante was upped thanks to the lunchtime find, on Wexford’s Great Saltee, of a showy Scops Owl becoming the 14th Irish record, the fourth record for Wexford and the fifth April record in total for the last 20 years.

…and, just as that second week was drawing to a close, it happened.

A monster Mega was on the loose - and, perhaps surprisingly, it was a Nearctic monster mega in to the bargain, a Great Blue Heron no less - and that particular arrival set the tone for many of the weeks that lay ahead of us, as birds from the Americas dominated the headlines for days on end (there’ll be much more on that trendsetting Heron later)….

But it wasn’t the relocating Pied-billed Grebe, that moved from Berkeley in Gloucestershire to Leighton Moss in Lancashire during the course of April 24th-25th that people spoke about as spring ended and the late June sun beat down across our collective nations. It wasn’t the pair of mightily impressive and eminently listable Hooded Mergansers that spent five late May days on Donegal’s Tory Island either…

No, much of the gossip and chatter centred on a remarkable set of vagrant Nearctic passerines that, at one point, just seemed to keep coming and coming and coming.

When the BBRC Rarities Report detailing the cream of the crop from the School of 2015 appears in October next year, one set of figures will really stand out as exceptional within the fabled pages of British Birds.

Cedar Waxwing Bombycilla cedrorum (0, 5, 3)

Three Cedar Waxwings! Out of all of the borderline extreme rarities that appeared throughout the 14 or so weeks of Spring 2015, this trio of well documented birds could well be the most remarkable set of records of them all.

Seldom ever on the radar of “rares that could turn up” - given their status they are a tough one to call and predict - the oft-intense westerly airflow that had already yielded thrushes and juncos just kept coming as June came around - and the first murmurings of something special being on the cards came on June 2nd, when a particularly aware non-birder reported a Waxwing at Rosehill on St. Mary’s (Scilly).

Given the weather at the time (a particularly deep low pressure system had tracked swiftly in from the Atlantic) the thought that this could well have been a Cedar Waxwing was, on this occasion, a wholly appropriate leap of faith but despite subsequent searching, the trail went cold and the species slipped from the radar once more (despite, as was pointed out at the time in the RBA Round Up that week, the first British record of the species coming along in June 1985).

Scilly birders would, of course, strike it lucky, later in the month but the focus swiftly turned from the extreme southwest to the extreme northwest of Scotland within just eight days of that first Scilly murmur…

The bushes of Scaranish, on Tiree, lie just a handful of island miles to the southwest of the bushes of Vaul - and they can now both boast the presence of a Cedar Waxwing within them.

The Vaul bird, seen in private gardens for nine late September days in 2013 was Britain and Ireland’s fifth-ever record of this elusive traveller - the Scaranish individual will become the eighth. And, as sightings go, the Tiree bird of 2015 really was pretty brief, not much more than a minute or so, but intrepid birder Keith Gillon managed to rattle off at least two rather gripping images - by way of quelling the usual Doubting Thomas’s - and all of those who weren’t on the scene in the winter of 1996 drew breath and winced a little.

They winced a little more not long after the news of the Tiree bird has began to seep in - here was another photographed Cedar Waxwing, this time courtesy of belated news of a two day bird seen southeast of Kilmer, near the Vandeleur Walled Garden in County Clare, present on June 3rd-4th (noted just a day after that unconfirmed report from Scilly…).

The Kilmer Cedar Waxwing became the first Irish spring record and the third in all - the first arrived on Inishbofin in October 2009, the second made it to the Mullet Peninsula in November 2012. Three birds, separated by three years each - the Irish west coast somewhere between June and November 2018 looks like a good bet…

…and then, just when the species was drifting off the radar once more - incredibly, up popped the St. Mary’s bird once again! A full 17 days between sightings, a Cedar Waxwing appeared in another St. Mary’s garden on 19th - and this time it managed to put on short, sweet show in Old Town (noted just three times between 1125 and 1250) before departing towards Lower Moors. Almost as quickly as it had (re-)appeared, it had disappeared once more, never to be seen again.

There is the outside possibility that the Old Town bird may even have been a second Scilly Cedar Waxwing, such was the gap between appearances on either side of the island but with Lower Moors and any number of other stands of suitable habitat through St. Mary’s central belt, there’s a chance that the Rosehill bird (well described by it’s one observer) did hide away. That said, 17 days seems like an awfully long time for a springtime Nearctic vagrant to stay put…

Three birds, or four, it doesn’t really matter. The arrival of early June Cedar Waxwings got the pulses racing - as did the quartet of what follows next.

Whilst the Mohawk-wearing wayfaring strangers may have captured the imagination most vividly throughout the tail end of the spring, not too far behind in the Transatlantic Travellers roll call of honour were a quite breath-taking quartet of North American thrushes - spread across at least three species - three of which occurred in the space of nine blustery and breezy days from the end of May into early June.

Adopted son of Mayo - and the Mullet - Dave Suddaby got the ball rolling on May 25th when he discovered Ireland’s first-ever spring Grey-cheeked Thrush in cover close to Termoncarragh. A rather warm-toned individual (invoking thoughts of Bicknell’s Thrush), Dave’s outstanding find spent a little time heading along the fenceline towards the lake before reappearing later that evening in the nearby graveyard.

A little bit of Irish birding history was duly made then and there and it was fitting that the site of the country’s first spring Grey-cheeked Thrush should lie within view of the site of the Blackrock Lighthouse - it was there on May 26th 1956 that Ireland’s one and only spring Swainson’s Thrush was found, freshly dead beneath the light.

…and, as we know, Swainson’s Thrush also played a major part in the bird news of Spring 2015 too - not one, but two arriving within a fortnight of each other in June.

First up, the well-twitched bird off the coast of Pembrokeshire, seen on Skokholm from 2nd-10th. Unless you’ve been on the Northern Isles in the last 15 years, this had become a real tough cookie to catch up with - Scilly’s last lingering bird coming in October 2000, two day-jobs have followed - hence the popularity of the Welsh bird this year.

A second Welsh record (the first was also found on Skokholm, in October 1967 - a bird which was also the first “live” record anywhere in Britain or Ireland) and a popular part of the spring agenda, it was followed by yet another Shetland record (the island chain’s dominance in recent years being quite an eye-opener) on June 16th courtesy of a confiding bird at Houbie, Fetlar.

Shetland’s first Swainson’s Thrush was found on Mainland at the end of October 1980 and it would be ten years after that the second for Shetland was found, on Fair Isle, at the end of September 1990. Another decade would pass before the third, another Mainland bird, seen in mid-October 2000 and, from then on, the islands have become the place to find the species - a further nine found around Shetland (including the Fetlar bird of 2015). A dozen birds in all - from an overall score of c.40 birds in total (overtaking Scilly too, 11 recorded there).

One Grey-cheeked Thrush, two Swainson’s Thrushes. Well, well. Whatever next? Veery of course.

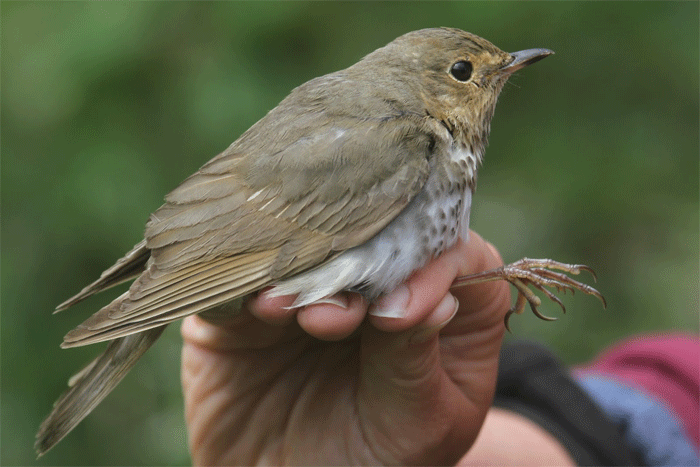

A mere five days hence from the Termoncarragh Catharus came what seemed the almost inevitable news - there was another “US” thrush on the go and this time, the rare-ante had been upped somewhat. The penultimate day of May found the hard-working staff of the North Ronaldsay Bird Observatory being confronted with something of surprise on the morning net-rounds - there in the mist-nets was Britain’s 11th (and the island’s second) Veery.

Post-processing, this funky little thrush from the Americas spent sometime in the grounds of the kirk through to mid-morning before appearing later in the day in the Holland House garden. May 31st saw the bird still in situ on the island, but it proved somewhat hard to find after appearing in the Observatory nets again - spending much of its time within the dense fuschias in the gardens at Holland.

After a blank was drawn on June 1st, the Veery then decided to show through to 4th - although it remained generally elusive, so elusive in fact that it was generally assumed to have departed Orkney airspace until the sighting of 9th.

We’ve had one spring Veery prior to this one, found on Lundy Island on May 14th 1997 - one of only four records for the southwest of England (it’s a ratio of 2:2 for Devon and Cornwall, the last of which was in 1999) - the dominance of Scotland has, much as with Swainson’s Thrush, been striking in the past 13 years, all six records from the 2000’s have occurred on Scottish islands, spread from Highland to Shetland and Orkney.

Almost coming in as a somewhat forgotten spirit amongst the Waxwings and Thrushes is actually the species that was the vanguard for all of this North American action - Slate-coloured Junco.

A full fortnight before the Mayo Thrush came this rather splendid songster on the stonewalls of Toab, Mainland Shetland - present for just the day on May 11th - he seemed to blend in quite beautifully with his subtle grey surroundings, the glaucous-green lichen adding a delicate additional tone to the powdery grey hues of this quality Nearctic visitor.

As was mentioned at the time, this lovely individual became the fifth for Shetland and May continues to be the one and only month for the species on the islands - all five records have been found between the 1st and 11th, from the first on Foula in 1966. Foula also collected the second Shetland Junco record, just over a year later and then it was Out Skerries turn, courtesy of another one day bird in May 1969. A gap of 34 years followed, with Skerries doing the business again - the bird present there on May 1st-9th being the only one of the five to stay for more than a day.

The Spring of 2015 just couldn’t stop on the one Slate-coloured Junco though - June 9th saw news reach us of the 2nd male of the year - another male making landfall on Cork’s Dursey Island to become Ireland’s fourth record, a county first and the third record of the 00’s (but the first since 2004). Just like the Shetland bird of a month earlier, this songster soon gave up the ghost, departing overnight.

(…and while we’re at it, we ought to mention the report of a third bird, reported a couple of times across June 14th-15th in the car park of the Logan Rock Inn, at the western tip of Cornwall. It all sounded reasonably convincing but never advanced beyond “reported” status).

Moving away from Passerines for a while, the time is right to head back to the Isles of Scilly for the bird that truly kick-started the spring…

Tales of woe (and much endeavour) were rife post the dipping of Britain’s first-ever Great Blue Heron, following a particularly angry Atlantic storm in December 2007. The first day or two of the events of April 2015 had a similar vibe too - though for many, there was a happy ending to be had this time around.

The conditions in which the two Scilly Great Blues couldn’t have been more different - a quick-fire, rippling low pressure that whipped a way from the eastern seaboard of the USA to the Western Approaches within less than 72 hours for bird #1; a somewhat genteel warm southerly airflow for bird #2 - but there were two things which were precisely the same for the two amazing discoveries - #1 the location - both birds appearing on the pools at Lower Moors and #2 the finder - Scilly resident Ashley Fisher clapping eyes on both birds and pronouncing them to both be Great Blue Herons. That really is quite something…

The first big twitch of 2015 really didn’t start that well - after spending time on Lower Moors and then in Old Town Bay on that first night of April 14th, the Great Blue Heron had other ideas the following morning as the boat from Penzance chugged it’s way across the foggy seas - lifting off from Old Town Bay around 11am. The minutes ticked by with “no further sign” and so it continued. It wasn’t in the bay and it wasn’t on Lower Moors either.

A brief sighting was had at Holy Vale later the same day, then it was back to Square One - the bird had lifted off in to the murk and couldn’t be relocated. A seemingly blank day followed on 16th until an early evening message mentioned “Possible Great Blue Heron 1w on Big Pool, Bryher”.

The rest is, as they say, history …

Staying on Bryher for the following four days, dozens of folk made the pilgrimage to Scilly and then it started to play games once more - on the afternoon of 20th, the bird decided that it had had enough of Bryher, duly popping across the channel to Tresco’s Great Pool.

A touch of inter-island hopscotch ensued, with commutes to Bryher and back following through 21st and then by the early evening, this second for Britain was back on St. Mary’s - roaming between its old stomping ground from the previous week - Lower Moors and Old Town Bay.

Bryher was the chosen location once more from 22nd-26th before returning for the final part of its 23 day vacation to the place it all began, the pools at Lower Moors, where it remained through until the blustery day of May 6th - the day-long preening session providing a somewhat significant clue as to an imminent departure.

How it got to Scilly is open to discussion. Some went for ship-assistance (they may be right) but in the wee small hours of putting the Weekly Round-Up to bed post Ashley’s amazing Second Coming discovery, I furiously typed the following on how the big boy may have landed on Scilly…

First thoughts - a vagrant Great Blue Heron makes landfall somewhere within the Western Palearctic - maybe moving off the Azores to tuck itself away in west or north Africa or around the Iberian Peninsula for the winter (three were logged on the islands between September and December 2014).

As the urge to move north kicks in, the bird’s first chance are the nigh-on PERFECT conditions that pushed so many “southern” migrants, oddities and vagrants to southwestern Britain and southern Ireland over the past seven days.

Logic still dictates that this must be the most favoured vagrancy explanation…

No sooner had the Scilly mega finally departed the far reaches of southwestern England, then a subtle pulse of warm, southerly-influenced air began to creep slowly towards Britain and although the conditions had been on the cool side all the way along England’s North Sea coasts, there was a small arrival of common migrants through much of Saturday May 9th.

The initial signs on an increasingly pleasant Sunday weren’t overly encouraging but it didn’t take long for a mighty yellow and green clad atom bomb of news to explode across PagerLand.

Citril Finch was a species no one in their right mind would have predicted to be emblazoned across the skies on that sunny Sunday morning of May 10th but that’s exactly what happened - and, for once, the stellar mega had the good grace to alight on the British mainland. Better still, it was found on the easily accessible (give or take a breathless mile and a half or so scurry) north Norfolk coast, on the dune side of the expansive range of pines at Holkham.

After a spot of early morning hullabaloo, this decidedly elusive (at first) little finch began to grow in to his role of contender for “Bird of the Spring” with some considerable aplomb as the morning minutes ticked by. After going missing since the middle of the morning a football match could have been played in the time it took for the Citril Finch to pop out from the pines once more and start to play ball.

A pattern quickly began to establish itself - a game of kick and run (so to speak) was on the agenda as the bird showed increasingly well in the deep dunes on the western edge of the pines, before all too easily being spooked (either by accidental clamour from excited birders or the motions of a passing hoppity-hop rabbit) and heading back towards the trees.

This set of events was repeated through the late morning and early afternoon - the bird often locating itself in one particularly dune hollow (the “Moltoni’s bushes”) where it would then depart and head closer to the safety of the hollows nearer to the pines. With each reappearance the views would often become more and more prolonged, five minutes would become ten, ten would become fifteen and so on and for all those able to get to the Norfolk coast in time, that particular Sunday will live long in the memory…

Norfolk’s Citril Finch was almost as unexpected as Fair Isle’s Citril Finch - found at The Haa, at the southern end of the island, on June 6th 2008. An unlikely contender for the British List, the Shetland bird underwent a rigorous review before finding a way on to Category A - vagrancy seemingly a remote possibility given the seasonal montane “up and down” movement and the “resident breeder” status in southern Europe.

However, that investigation of the Fair Isle bird also confirmed that this was a species that was rare in captivity and that there was also a history of extralimital records in southern and central Europe along with an at-present Category D record from Finland…with no hints of captive origin on the Haa bird, acceptance was assured. Norfolk’s incredible second British record will have no problems in following suit - indeed, word has it that there were some exceptional numbers of Citril Finches present in some parts of the species range earlier this spring - which makes life all the more easier too.

For a few early morning risers, the Holkham Citril Finch managed some good, though mainly brief views the following day, until just before 6.30am when it flew from the edge of the pines and away in to the dunes and much further a field too - off towards Scolt Head Island and beyond, never to return.

For some of those morning visitors to Norfolk that day, if they lingered long enough, then they were just about to land another cracker for their money…

It all started with news of a female Subalpine Warbler being seen briefly in the famous Blakeney Point plantation, just after 9am. Whilst a lovely thing to see, the fact that it was both brief and not seen subsequently meant that the hike west from Cley really wasn’t on the agenda.

That changed a little while later when news began to circulate of a male, also in the Plantation. Two Subalpine Warblers was quite something and the thoughts began to turn to a trip to the Point was more likely. Given the warm south to southwest wind and the fact that Norfolk had hosted a crinklingly rare finch just hours beforehand, some minds were already drifting towards an all-together more appealing potential outcome to the double discovery of warden Paul Nichols.

BP stalwart Andy Stoddart was already on the Point when Paul had located the female Sub-A and, by the time he arrived at the Plantation, Paul brought news of the male. And what a striking male he was too - all pastel tones, soft and subtle of hue - and to top it all, there was also the diagnostic dry, Red-breasted Flycatcher-like rattle for good measure - this was, most certainly, a nailed-on Moltoni’s Warbler…

The bird showed well in both the Plantation and the nearby Laboratory tamarisks to the first visitors (some of whom went along working on nothing more than rare-based intuition), calling occasionally and sometimes performing side-by-side with the rather bright female Subalpine too. Quite what species she actually was remains the subject of debate; several observers saying that she definitely “rattled”, others suggesting she gave the definitive “tac” of a Western Subalpine.

With a favourable tide, many birders were at least able to enjoy an easy ride one-way and all those who managed to make it to the Point that day went home with views of both birds, many feeling sure that the male Moltoni’s Warbler was in the company of a female Moltoni’s Warbler.

While the female will never get the green-light, the male will breeze through (on plumage alone, though the call was recorded for posterity too) and he seems likely to become the fifth British record - the first was a male collected as a specimen on St. Kilda in June 1894 (plumage and genetic analysis confirming, beyond doubt, that it was male Moltoni’s Subalpine Warbler) with far more recent records coming from Shetland - the two males on Shetland in May 2009 (on Mainland and on Unst) and the unequivocal female, trapped, ringed and DNA analysed on Fair Isle in May 2014…

…which takes us nicely on to…

With Fair Isle in our minds, it would be remiss not to detail the second Moltoni’s Warbler of Spring 2015 - a delightful male making himself known in the Observatory garden just four days after the one-day Point bird/s on May 15th. Eventually worked his way down the island - where it would often show well in the ditches close to the road near Midway - he too uttered the occasional rattle, just in case there were any doubts over his in-field appearance...

After a solid 12 day stay, the first-summer, first Fair Isle male Moltoni’s was gone - but not before a sample was obtained for a little bit of DNA work to be undertaken. Within a month, the answer was back - there’d have been uproar if a bird looking as it did (let alone sounding as it did) was anything other than of Moltoni’s extraction - but for all those who cared, the answer was plain as day. Fair Isle had a second example of this most recent of splits within a year. The key question remains, how many more have there actually been?

And it was a question which was asked far more widely after two in the space of five mid-May days - much careful photo analysis may provide one or two more but to date, well, there’s not much being offered up. But with 115 years between Record 1 and Record Two (and Three) it seems likely that one or two have slipped through the net…

…which hopefully isn’t the case with the third male Moltoni’s Warbler seen this year - another delicate pastel-shaded beauty noted on the fences near the Balranald RSPB reserve on North Uist, in the Outer Hebrides on June 4th. Despite the lack of any vocalisations, this striking bird hollers “rare!” in every online image. Is there enough Committee confidence in the suite of characters exhibited by males in their spring garb?

A peep at the Rarities Report in just over a year’s time may tell us all we need to know.

When many of the nation’s active listers tucked themselves under their Peter Rabbit (or maybe Peter Griffin?) quilt covers on the Friday night of April 24th, few would have imagined waking the next morning, wiping the sleepy-dust encrusting their all-seeing eyes to one side to read news of a “probable Hudsonian Godwit” on the one-time Somerset Levels.

…fact is always stranger than fiction and it wasn’t long before that “probable” was undergoing a somewhat significant upgrade - one of Britain’s longest standing blockers was, like an Amazonian slash’n’burn forest, ready to fall. Timber indeed.

Within five minutes of that first report, the word was out - this really was a Hudsonian Godwit and it showing at Meare Heath. For anyone not in their 40’s or beyond, this was a massive rare, a monster rare, a Giga rare - perhaps not in the same mould as say Houbara or Pallas’s Sandgrouse but one of the most anticipated birds of recent times.

As with so many other rarities these days, the Saturday news (and prime location for widespread twitching, given the proximity to major road networks) ensured a steady stream of happy birders pitching up on-site enjoying this divine female Hudwit in the company of some Icelandic travelling companions.

As it happened, the bird had been seen and suspected as being a Hudsonian Godwit the night before when local birder Tom Raven chanced upon the bird in a post-work, pre-weekend visit. Not daring to quite believe what he was seeing, a brain-melding night of research, of Google Images and field guide thumbing all still suggested to Tom that, yes, his mind wasn’t playing tricks on him - but for a bird of such magnitude, he set his alarm for the crack of dawn and went back to nail it…

…and, as everyone knows, he nailed it with some panache - the entire suite of characters that enabled the big call of Hudwit were all there, lining themselves up to be ticked off one by one. The news was out, the chase was on and a tick was had by all. Well, almost all.

After showing for seven hours or so, the godwit headed west and didn’t appear again that day, dashing the hopes of those who had scorched from one end of the country to the other. She didn’t show the next day either. Or the day after that. The trail was getting colder by the day.

Thankfully, she materialised again amongst the Black-tailed Godwit flock, in the very same spot, on April 29th and continued to show off and on until the end of the weekend on May 3rd - by which time 1000’s of birders had journeyed to this remarkable area and the 32 year gap between “available” records was closed.

The dates of occurrence for the Somerset bird and the returning spring bird in East Yorkshire have an uncanny resemblance to one another - the 2015 individual was seen between April 25th-May 3rd; the British first (on a second outing to Blacktoft Sands) arrived on April 26th and departed on May 6th. As regular readers will know, ditto students of all things rare, the 1st for Britain spent several days avoiding a firm identification in the autumn of 1981, leaving Humberside on October 3rd, only to emerge weeks later in Devon, where it lingered until mid-January 1982. Our only other record was a single observer sighting in Aberdeenshire in September 1988.

Few birds have lasted so long in the modern era of twitching - what’s the next one with 30+ years on the clock to fall?

Before departing back to our final chunk of Passerine Pleasure, let’s give a little nod to another bird that passes through the colossal Hudson Bay, in Canada’s northeastern territories en route to breeding grounds in the far northwest of the country - Hudsonian Whimbrel.

The BOURC-TSC recommended the splitting of this long-haul vagrant in 2011 - 10 of the dozen accepted land-based records (across both Britain and Ireland) falling on or before the proposal was published. Of those, multi-observed individuals had been seen in Gwent, in May 2000 and again in 2002, in Cumbria for much of the summer of 2007 and then on Scilly, on St. Mary’s for most of September 2008.

Given the years that have elapsed since that Walney Island Hudsonian Whimbrel, the appearance of one in West Sussex this spring meant that a crowd was almost guaranteed - found on June 9th, it stuck it out in Pagham Harbour all the way through to the end of the month at least (with a Terek Sandpiper thrown in to the mix for good measure…).

A double-bill of Hudsonian shorebirds within just a few weeks. Who’d have thought it?

…and so we reach the epic conclusion of an invigorating passage of birding time. The flip-flop between Passerines and Non-Passerines throughout the spring was highly entertaining, even though the latter was a little top-heavy t’wards April.

Ardent rarity watchers will be only too well aware of the old adage that “the big one travels alone” and, often as not, the more days that are ticked off the calendar in June, the better the rarity will become. Put to the two together and you have birding gold.

Avian nuggets discovered in the concluding weeks of spring included the immaculate male Eastern Black-eared Wheatear that made it’s way to Hampshire’s New Forest, spending much of June 13th performing to all comers at Acres Down and, more surprising still, the photographed Eyebrowed Thrush found on Shetland, over on Whalsay, on the amazing date of June 20th (the fourth spring record in all, following on from Scottish May birds of 1981 and 1995, along with a second Spring bird for 1981, seen in East Yorkshire in April that year).

For a good few 100 birders though, the grandest of Grand Finales came courtesy of an immensely pleasurable debut sortie for many to a gem of an island off the coast of north Wales - Destination? Bardsey. The quarry? Male Cretzschmar’s Bunting.

Until now, this bird has been in the exclusive domain of the Northern Isles; three for Shetland (that’s three for Fair Isle don’t forget) and two for Orkney. The events of June 10th this year changed all that as the brief encounter of a fine male Cretzschmar’s Bunting on Bardsey Island set many a hearts a flutter - working out the if, but and maybe of twitching logistics to an island that everyone knew about, but few knew just how to get there…

As the hours passed on that 1st day of discovery (a date shared with Britain’s very first record, on Fair Isle 48 years previously) any thoughts of getting to this prettiest, most strikingly beautiful of offshore locations seemed irrelevant - despite much searching, it seemed as though the bird had made it’s escape already.

Further diligent efforts were employed throughout the next day - and still there was nothing to show for the collective efforts of the island’s birders. As we all know now, everything changed for the better come 12th, the resplendent male Cretzschmar’s had found a way to the south end of the island and it seemed everything was game on again.

Wrong…

After the shortest of showings, the bird went missing once more - no further sightings were had throughout the rest of 12th or at all on 13th - but finally, smiles were had all round as the morning of 14th saw him take up a temporary residence around the lighthouse compound and this was were he’d stay for just shy of a week - a week that would see a monumental effort from warden Steve Stansfield and the Bird Observatory staff along with boatman Colin Evans to ferry and guide visitors, 12 at a time, over and on to the island on what turned out to be one of the most well-organised twitches of recent (or any other) time.

(In a wonderful piece of symmetry - goodness how I love symmetry - the Bardsey Bunting’s dates ended up as being identical to that very first bird on Fair Isle; June 10th-20th. Beautiful…just beautiful…).

The Bunting came and went from the seed in the compound, often giving several bursts of song from the rocky outcrops behind the out buildings, as birders too came and went from the site, almost everyone heading home happy (what’s not to love about a thoroughly well organised event like this, with glorious scenery and a cracking rare in to the bargain?)

Come the end of the year, the Bardsey Bunting Event may well be one of the most talked about highlights of 2015 - but we’ve yet to find out what gems lie ahead in the second half of the year. There’s an awfully long way to go, in birding terms, before we can pronounce further on 2015, but for now at least, this exploration of the spring’s cream-of-the-crop, top-of-the-class wide and varied (and in no small measure, surprising) set of species will give folk lots to talk about…

Has it been the best spring ever? Has it actually bettered the classic 1990 became an online topic of discussion. Trundling down this particular avenue is a bit of a one-way street - both springs being markedly different, both bringing a whole host of unexpected treats with them.

Do 2015’s widely twitched second record (Great Blue Heron), third record (Hudsonian Godwit) and sixth record (Cretzschmar’s Bunting) along with the sixth, seventh and eighth records of a much sought-after rare (Cedar Waxwing) “better” the very finest that 1990 could offer?

Its a pretty dangerous game to play - going head-to-head with the often stellar spring weeks of 1990. There was the outrageous first (Lundy’s Ancient Murrelet), the oft-predicted first (Scilly’s Tree Swallow), the eternally under-rated first (long awaited, still-waiting split) (the East Sussex Least Tern) and the OMG moment that came long before OMG (and WTF for that matter) existed, courtesy of a Shetland monster (the Hillwell Pallas’s Sandgrouse) - all of these make it a particularly heavy line up to go up against…

Rather than compare and contrast and try and find ways to formulate why one spring was “better” than the other, it would be more circumspect, and far more enjoyable, to just sit back, relax and savour the many magic moments of yet another spectacular few spring weeks.

There we go…that’s more like it isn’t it?

Breathe everyone, just breathe…

Mark Golley

Cley, Norfolk

7 Jul 2015