New Light on an Old Traveller

Great Reed Warblers breeding in Kazakhstan follow a unique, curved migration route to East Africa – and make a remarkable two-step journey home each spring.

Unravelling the mystery of a long-distance migrant

How do birds evolve their migration routes as their ranges expand across continents? A new study published in the Journal of Avian Biology by Staffan Bensch and colleagues at Lund University has shed light on this question using the Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus.

Using miniature light-level geolocators and multisensor loggers, the researchers tracked Great Reed Warblers breeding in south-eastern Kazakhstan – the species’ easternmost range – and uncovered both a surprising migration route and a previously unknown spring stopover site.

Not the route anyone expected

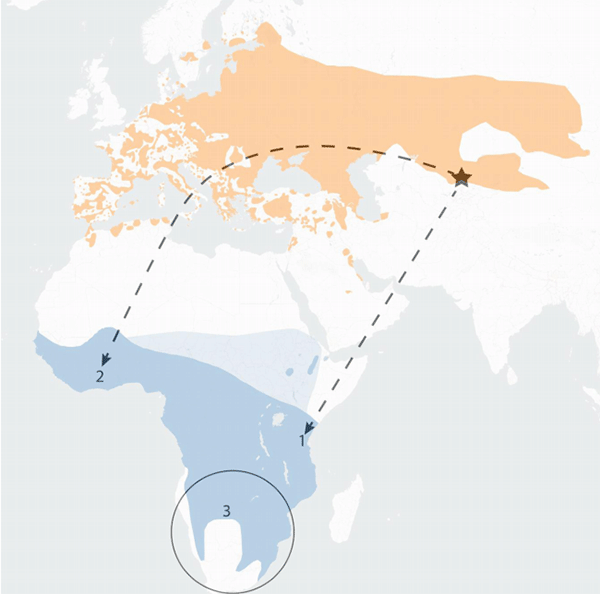

Genetic studies suggest that Great Reed Warblers in Kazakhstan descend from western European populations. If their migration programme had simply followed ancestral compass directions, they should migrate south-west towards Africa. Instead, the new tracking data show a more complex path: the birds first travel west through Central Asia before turning sharply south-west to reach East Africa.

This curved route, the authors suggest, represents a major evolutionary adjustment to maintain traditional African wintering grounds even as the species’ breeding range extended thousands of kilometres east. It challenges assumptions that small songbirds are tightly constrained by inherited migratory directions and reveals a surprising flexibility in their navigation systems.

Discovery of a spring staging site in Iraq

One of the most remarkable findings is the identification of a spring staging area in the Tigris–Euphrates river system of southern Iraq. The Kazakh warblers leave their African wintering sites as early as February and spend up to two months there before resuming migration to their breeding grounds.

This “two-step” spring strategy – a long stopover halfway home – is unlike any previously described in Palearctic–Afrotropical migrants. The birds appear to use the fertile wetlands of Iraq to rest and refuel before crossing the vast, arid deserts that separate their breeding territories from Africa.

Tracing evolutionary history through migration

By combining genetic, geographic, and behavioural data, the team reconstructed how these unusual routes likely evolved. Following the last Ice Age, Great Reed Warblers spread eastwards from Europe. Rather than adopting closer Asian wintering areas, the new eastern populations retained ancestral African destinations – effectively bending their routes to preserve them.

Such “curved” migration paths are rare among European–African migrants but have been documented in a few other species that colonised Asia in recent millennia, including Common Swifts and Willow Warblers. The findings underscore how evolutionary history can shape present-day migration patterns in unexpected ways.

Why it matters

Understanding how birds adapt their migration routes to changing geography, climate, and habitats is critical in an era of global environmental change. As stopover sites and wetlands along major flyways face increasing human pressure, knowledge of species-specific routes becomes vital for targeted conservation.

The discovery of the Iraq staging area, in particular, highlights an unrecognised wetland of major ecological significance for long-distance migrants. Protecting such sites may be essential for sustaining populations that depend on them during their most demanding journeys.

A window into evolution in motion

The Great Reed Warbler’s newly revealed journey – looping west across Asia to winter in Africa, then pausing for weeks in Iraq before returning to Kazakhstan – offers a vivid example of how migration evolves across time and geography. It demonstrates that even deeply rooted migratory programmes can bend and adapt, creating intricate paths that connect continents, ecosystems, and evolutionary histories.

October 2025

Get Breaking Birdnews First

To get all the latest breaking bird news as it happens, download BirdAlertPRO for a 30-day free trial – no payment details required – and access exclusive first-time subscriber offers.

Share this story