Harpy Eagle attacks tourist in Amazon rainforest

To date, Harpy Eagle attacks on humans have been anecdotal, but now scientists have documented the first case of the huge raptor attacking an adult in the Amazon rainforest.

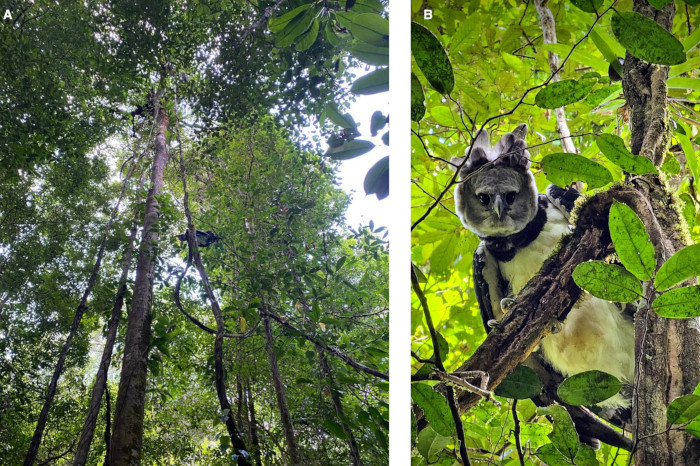

In the heart of French Guiana’s rainforest, a silent sentinel watched from the canopy – a Harpy Eagle, among the world’s largest and most powerful raptors. What followed has shaken assumptions long held by biologists and naturalists alike. For the first time, a scientifically documented case confirms a Harpy Eagle attacking an adult human, adding new weight to theories about the evolutionary pressures large raptors may have once exerted on our early ancestors.

Until now, most records of Harpy Eagle aggression towards humans were anecdotal, often tied to nest defence or captive birds. This incident – involving a 29-year-old woman on a tourist trail – occurred in a wild, undisturbed part of the Amazon, far from any known nest. The attack was unprovoked and vicious, with the eagle gripping the back of the woman’s head and inflicting deep scalp wounds before being driven off by her partner.

Apex Raptors in a Human Context

While the Harpy Eagle’s diet typically includes medium-sized mammals like monkeys and sloths, this case reveals a more complex behavioural potential. Theories suggest the eagle may have been disturbed during a hunt or defending a previous kill. Regardless of cause, the researchers argue that this event warrants a re-examination of the long-dismissed idea that large eagles can pose predation risks to humans – particularly infants or lone individuals.

This idea is not without precedent. The famous case of the Taung Child – a 2.5-million-year-old Australopithecus with talon damage to the skull – has long fuelled debate about raptors' evolutionary role. The current study directly links this ancient possibility with a modern case, suggesting these threats may not be entirely relics of the past.

Sociality as Shield

One theme emerges strongly from the incident: the importance of sociality. The attack occurred when the woman was briefly isolated from her group, and researchers argue that group cohesion may have prevented a more serious outcome. In evolutionary terms, this reinforces the view that living in groups offered early primates—including hominins—protection against aerial predators.

Had the woman been alone, the attack might have been fatal, given the eagle’s size and power. This situational insight adds a compelling real-world dimension to theories of social evolution, especially regarding anti-predator strategies in forested environments.

Balancing Knowledge and Conservation

Though the paper adds a dramatic entry to the scientific literature, the authors are cautious. Harpy Eagles remain a vulnerable species, threatened by deforestation and persecution. The fear such reports may provoke could have damaging consequences, especially in regions where local communities already harbour suspicions about large predators.

Indeed, the researchers emphasise that this incident should not be interpreted as evidence of widespread danger. Rather, it offers an opportunity to better understand predator-prey dynamics and the evolutionary context of primate behaviour, including our own. Awareness, they argue, need not lead to fear – but instead to respect for the ecological role these majestic birds continue to play.

24 April 2025

Share this story