Book Review: Britain’s Birds

An identification guide to the birds of Great Britain and Ireland: Second edition

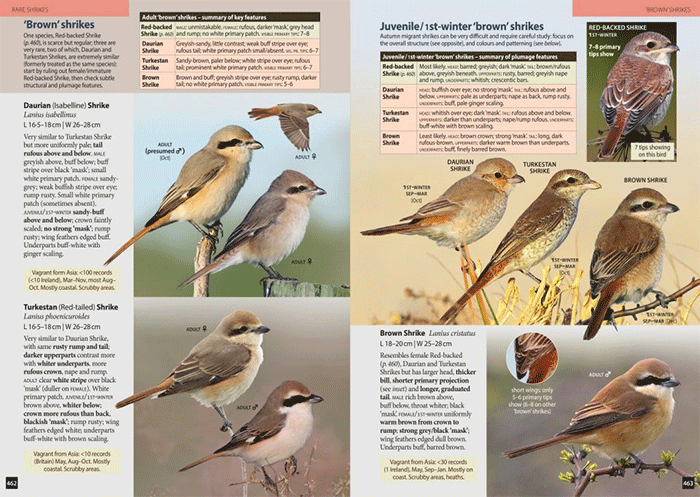

This new publication is a fully revised and updated second edition of the already popular title first published in 2016. In my review of the first edition I was happily able to dispense with my long-standing prejudices against photo field guides. As I explained there, the images in this guide have been chosen so well that the usual problem of badly lit and badly posed birds - so prevalent in many such guides - has been largely eliminated. The photographs selected here are genuinely representative of the species concerned and are, in most cases, as informative as a high quality painted field guide illustration.

Having previously established therefore that this is already a fine guide, it’s time to look at the revisions which have taken place since the first edition. Perhaps the first change to note is in the title, where ‘Britain’ has become ‘Great Britain’, and there is also a new, now side-on, Robin on the front cover.

Within the book itself the updates are significant, representing a complete overhaul of the species and subspecies coverage so as to keep abreast of recent additions to the British and Irish lists. This is all now as up to date as it is possible to be, with those announced in the 51st BOURC Report (published in February this year) all incorporated. Thus we now have welcome appearances by columbarius Merlin, polaris Little Auk, alpestris/praticola/hoyti Shorelark, Dalmatian Pelican, White-rumped Swift, halimodendri Lesser Whitethroat and Eastern Orphean Warbler and (from previous Reports) a long list of other additions too. Of course the book will be immediately out of date (it already needs updating with mandtii Black Guillemot) but this is a problem the authors can do nothing about.

The latest IOC/BOU/IRBC taxonomic announcements are also included, with full treatments afforded here to the latest splits - Hudsonian and Eurasian Whimbrel, Royal and West African Crested Terns, and Eastern and Western Black-eared Wheatears.

Given the space constraints of a field guide, the updated text accounts remain admirably comprehensive and, given also the complexities of some species and species pairs, the authors have continued to do an excellent job of synthesising a lot of information into an easily digestible form. The difficulties surrounding ‘Eastern Stonechats’ are well addressed, for example, with an excellent brand new double-page spread. However, the new Eastern Yellow Wagtail account is perhaps a little too brief, suggesting, for example, that only ‘blue-headed’ adult males exist (in fact there are four subspecies – all potential vagrants to Britain – with very different adult male appearances). I would also have liked a bit more content on, for example, large gull plumages and on redpolls (both of which are also overly compressed) but at the end of the day this is a field guide, and more detailed treatments of these topics are available elsewhere.

I only found one or two other minor quibbles. The Yellow Wagtail account is a little confusing by failing to distinguish between hybrids (which occur between species) and intergrades (which occur between subspecies) whilst the text fails to mention the harsh call of cinereocapilla (although this is mentioned for both of the other ‘southern wagtails’, iberiae and feldegg). In the Common Redpoll account it was disappointing to see the term ‘Mealy’ used as though it were a synonym of the species name instead of being simply the colloquial name of the nominate subspecies.

Interestingly, the term ‘race’ has been excised from the book, replaced with the (far preferable) ‘subspecies’. The updated treatment of subspecies is understandably variable in its thoroughness. Some, such as Britain’s Wrens, receive commendably detailed treatment whereas other more obscure vagrant taxa, such as polaris Little Auk, receive just a passing mention. In addition, the content on blythi and halimodendri Lesser Whitethroats is now clearer than it was before although the account for fuscus Lesser Black-backed Gull still only refers to non-field-provable adults, omitting any discussion of the more identifiable 2cy birds.

Of course the updates are not just confined to the text. There has also been a complete overhaul of the images with more than 800 new (and better) photographs, for example those of Barolo Shearwater and Zino’s, Fea’s and Desertas Petrels, and also revised and improved layouts. This has resulted in an increase of 16 in the overall page count since the first edition.

Sharper eyes than mine spotted a tiny number of misidentified images in the first edition and these have all been corrected here. The ageing and sexing of the images has also been revisited (the ‘1st-winter’ Glaucous and Iceland Gulls of the first edition are now hedged as ‘Juvenile/1st-winter’). A further very useful development is the inclusion (where known) of the month in which a particular photograph was taken. It is good to see that RBA’s own Chris Batty has been used as a consultant to the project, and the revised image captioning will certainly have benefited considerably from his scrutiny.

The maps have been updated too, following some criticism of the first edition. These include new mapped ranges for Balearic Shearwater, White-tailed Eagle, Marsh Harrier and Bearded Tit whilst the Golden Oriole map has been removed entirely and new ones created for Cattle Egret and Water Pipit. The map for Common Crane, however, does not show its new home in the Fens and Yorkshire. Capturing dynamic ranges and occurrence patterns in maps is always going to be problematic, however, and, as in all field guides, these thumbnails are best used as a rough guide only, with further detail easily available in detailed atlases and county avifaunas and reports.

The book concludes, as before, with Appendices detailing Category D and E species and a comprehensive British and Irish List which identifies the list category for each country and all appropriate conservation designations. All these sections have of course been fully brought up to date.

This is therefore a further improvement on what was already an outstanding field guide. The constraints of space and time and the difficult job of melding text and images into a pleasing final design will always mean that occasional errors slip through the net. However, the few mistakes which crept into the first edition have now been addressed and there are even fewer things to quibble with now. This is still by far the best photographic guide to Britain’s birds.

Andy Stoddart

18 May 2020

Share this story