Adapt or Be Blinded by the Light

The emergence of visual adaptations in urban birds raises concerns that survival now hinges on keeping pace with human-induced environmental upheaval.

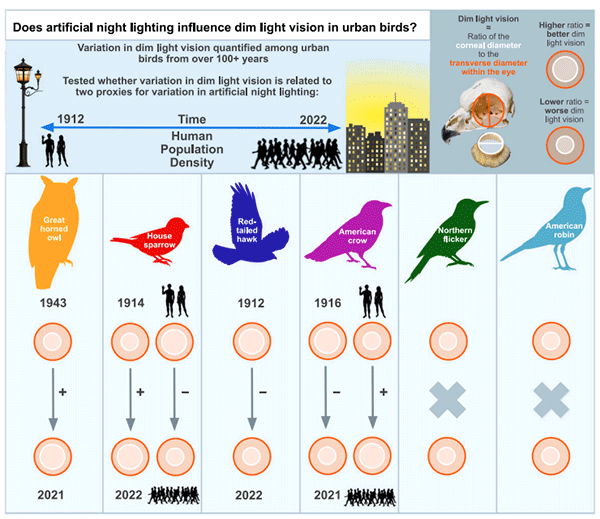

Artificial light at night (ALAN) is transforming the ecological and evolutionary landscape for birds. A study by Margaret Wolf and Clinton Francis, published in iScience, examines how ALAN may be shaping dim light vision in urban birds by altering eye morphology. Using over a century of museum specimens from six common urban-adapted species, the researchers found evidence that changes in urban lighting conditions correspond with changes in the skeletal structures of the eye - specifically the orbit and sclerotic ring diameters - which determine a bird’s ability to see in low light.

ALAN is known to affect bird behaviour and physiology, from disrupting melatonin production to changing foraging patterns. However, this is the first evidence that ALAN may be driving evolutionary change in sensory systems. The researchers examined whether changes in dim light vision correlated with two proxies for night-time light exposure: year of collection and human population density at the collection site.

Winners, Losers and the AmbivalentHouse Sparrows and Great Horned Owls showed increasing dim light vision over time, consistent with the “temporal niche shift” hypothesis, which predicts improved night vision to exploit new activity windows enabled by urban lighting. In contrast, American Crows and Red-tailed Hawks exhibited decreasing dim light vision, supporting the “protection” hypothesis - that reducing light sensitivity helps mitigate ALAN’s physiological costs, such as melatonin disruption and immune suppression.

Interestingly, American Crows showed an apparent contradiction: dim light vision decreased over time, but increased with human population density. The authors suggest this may reflect a trade-off between ecological opportunity and physiological cost - where dim light vision may be advantageous in moderately lit areas but counterproductive in intensely illuminated environments.

Northern Flickers and American Robins showed no clear trends. These species may be less exposed to light at night due to behavioural traits like cavity nesting (in Flickers), or may experience inconsistent lighting conditions due to partial migratory behaviour (in Robins).

Inside the Avian EyeChanges in dim light vision corresponded with specific anatomical shifts. In House Sparrows and Red-tailed Hawks, changes were driven by modifications in orbit diameter, while in American Crows, the sclerotic ring played a larger role. In Great Horned Owls, both structures were tied to body size rather than light exposure, though the relationship with dim light vision remains suggestive.

The findings indicate that different species may evolve different morphological pathways in response to the same environmental pressure. This has important implications for predicting species responses to urbanisation and understanding which lineages are more evolutionarily flexible in their sensory systems.

Implications for Conservation and Urban PlanningWith artificial light increasing globally by 2% per year, these findings underscore the need to factor ALAN into urban conservation planning. Light pollution has already been linked to behavioural changes and population declines in some birds. If it also drives evolutionary change, the ecological consequences could extend across generations.

Understanding how birds adapt - or fail to adapt - to novel sensory environments is critical for forecasting urban biodiversity trends. This study highlights the value of museum collections for detecting long-term evolutionary changes, and calls for future work to examine whether improved dim light vision indeed results in expanded nocturnal activity and enhanced fitness in real-world settings.

Further DirectionsFuture research should assess whether these anatomical shifts in eye geometry translate into functional changes in vision and behaviour. Additionally, exploring how artificial light interacts with other urban stressors such as noise and food availability could offer a fuller picture of urban evolution.

By illuminating the eye’s subtle evolutionary responses to artificial light, this research sheds light - quite literally - on how human-altered environments are reshaping animal biology in the Anthropocene.

July 2025

Share this story