The Lynford crossbill conundrum.

Two-barred or not Two-barred? That is the question!

by Marcus Nash

Lynford arboretum, in the Norfolk Brecks, seems particularly attractive to Two-barred Crossbill. I remember seeing my first there, a female, way back in 1990. Admittedly, none were reported there from then until February 2012, when a pair appeared briefly one morning. However, as the latest invasion started last summer, a group very quickly appeared at Lynford, with up to 4 birds reported from 21st July until 29th. Whether it was any of these same birds which remained in the area is unclear, but a juvenile was reported erratically through August and the first half of September, then up to 4 birds again through the second half of the month and October. At some point during this period, a rather controversial bird turned up at the site. Certainly seen from November 2013, it has remained throughout the winter.

On first glance, it looks distinctly underwhelming. Initially reported as a male Two-barred Crossbill, it has subsequently been put down variously as either a wing-barred Common, 1st year Two-barred or even a hybrid. Unfortunately, it has been rather elusive through much of its stay, being reported at Lynford only sporadically. Given questions over its identity and the difficulty over seeing it, I had made no effort to find it myself over the winter. As better photos emerged, I became more and more intrigued. It appeared to be a very interesting bird and potentially rather educational, and I wondered whether it was being dismissed unfairly. However, despite trying several times to see it, I had failed consistently. On 23rd March, another group of three more obvious Two-barred Crossbills appeared at Lynford, and this prompted me to try again. Whilst we failed to see the obvious birds, those present on 25th were rewarded with prolonged and at times very close views of the controversial bird, as it fed in deciduous trees and came down to drink. I returned again on 27th, and this time saw the three clear-cut 1st winter Two-barred Crossbills (2 males & 1 female) as well as the bird in question. Following discussion with those around me, particularly James McCallum and Dick Filby, I was prompted to put pen to paper to try to dispel a few myths and narrow down the debate.

Probably the most important thing to do with a bird such as this, is to establish its correct age. On close examination, the Lynford crossbill shows an apparent moult contrast in the greater coverts and retained juvenile tertials, both discussed in more detail below. The colour of crossbill body plumage can vary with diet, more particularly lacking red colour if it is deficient in certain carotenoid pigments, but the majority of birds still show particular colours or combinations which are related to age and sex. For example, van Duivendijk (2010) states about 1st winter Two-barred Crossbill “some 1w male completely orange, others nearly still complete juv at same time with mix of green-yellow and red-orange underparts and upperparts” and even for 1st summer “rest of plumage very variable, some males already entirely red” which implies that some are not yet totally red. The Lynford crossbill shows a mixture of red-toned adult body plumage mixed with patches of yellow, particularly around the face and upper breast, as well as more strikingly in a band across the lower rump, which would seem to be most consistent with a 1st winter Two-barred Crossbill. Interestingly, the other two 1st winter male Two-barred Crossbills currently at Lynford also show a similar mix of red and yellow body feathering, to a greater or lesser extent. This all points to the controversial crossbill being a 1st winter. Once correctly aged, it is then important to look at the individual features in more detail.

Tertial Tips – the Lynford crossbill lacks the obvious pale tips to the tertials usually quoted as diagnostic of Two-barred, and this has led some to condemn it out of hand. However, it appears these are only rarely replaced in the post-juvenile moult, so a 1st winter Two-barred would most likely have retained all its juvenile tertials. The white tips of juvenile Two-barred tertials are also much smaller than the equivalent adult feathers or just a thin white fringe round the end of the feather and, by this time of year, these would be heavily abraded. Indeed, the other three Two-barred Crossbills at Lynford recently have also lacked white tertial tips and both the controversial bird and those three show very worn feathers. In addition, in photographs taken of the controversial bird back in November, it appears to show slightly more white here. So the lack of white tertial tips is entirely consistent with a 1st winter Two-barred.

Wingbars – the other feature which immediately seems at odds with Two-barred is the greater covert wingbar, which is rather thin and does not appear to bulge significantly towards the innerwing. However, as with the tertial tips, all may not be as simple as it seems. Two-barred Crossbill has a very protracted breeding season and therefore very variable timing, and correspondingly also extent, of the post-juvenile moult. Consequently, the appearance of 1st winter birds can vary substantially between individuals. BWP (Cramp et al, 1998) states “Advanced birds similar to adult, but juvenile flight feathers, tail, usually all tertials and often at least outer greater upper-wing coverts retained. In more retarded birds, many juvenile wing coverts retained, as well as scattered juvenile feathering on body.” This is evident on the other 1st winter Two-barred Crossbills currently at Lynford – one male has seemingly replaced all its greater coverts, whereas the other appears to have retained a number of outer greater coverts, resulting in a clear moult contrast and a ‘step’ in the greater covert wingbar. BWP goes on to say “In 1st adults… when coverts and tertials all juvenile, white tips partly wear off”, suggesting that it is not impossible to find some 1st winter Two-barred Crossbills with completely retained juvenile greater coverts.

On close examination of the controversial bird, it would indeed appear that most of the greater coverts are actually retained juvenile feathers, with a very restricted white tip and slightly more white extending a short way up the outer web, consistent with the illustration in Svensson (1992). In addition, when seen well, it would appear that one or two of the innermost greater coverts have a much more extensive white tip, with a more squared off border to the dark base, consistent with adult-type feathers. This is visible in some photographs as a slight bulge in the greater covert wingbar where it meets the tertials, but can be difficult to see in the field, especially when viewing from below. This would appear to be entirely consistent with a 1st winter Two-barred Crossbill which has retained the majority of its juvenile greater coverts. A similar bird with substantially retained juvenile greater coverts was photographed in Helsinki, Finland in December 2008 and is shown below.

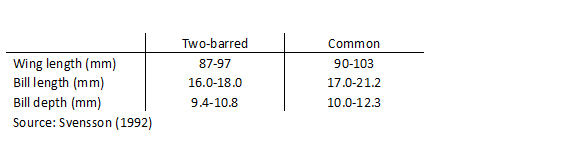

Biometrics – Two-barred Crossbill is generally deemed to be a bit smaller than Common Crossbills and with a slightly smaller bill. Van Duivendijk (2010) states “Generally more slender and less strongly curved mandibles than other crossbills, making bill look longer (but variable as in all crossbills)”. Some observers have suggested that the controversial bird is as big as a Common and that the bill looks too heavy. To my eye, the bill of this bird did look slim or weak compared to a Common bill. Whilst I didn’t see it together with the other Two-barred Crossbills, photographs of all the birds together suggest that it is similar in size. However, looking at published biometrics, there is actually a very large amount of overlap both in size and bill size between Two-barred and Common, suggesting that these are not diagnostic. Harrop et al. (2007) also states that “The bill of bifasciata [the Eurasian race of Two-barred Crossbill] is heavy and often indistinguishable from that of Common Crossbill”. Measurements from Svensson are shown in the table below.

Body plumage / colour – male Two-barred Crossbill is generally assumed to have pinkier-red body tones than the more brick-red of Common. In the field, the Lynford bird appeared to me to have some raspberry red tones, especially to crown and flanks. However, other observers have questioned that it is not pink enough and it is true that it looks rather red overall. Again, this may not be the issue it first appears. BWP actually states “Head and body of advanced 1st adult male orange- or rosy-red, less bright and less deep rosy than in adult male”. In addition, Two-barred Crossbill has scapulars and some mantle feathers with very dark bases, and this certainly seems to be the case with the Lynford bird. BWP also states that male Two-barred shows “dusky grey cast on mantle & round shoulder” and this is shows well in the attached photos of the bird in question. So the body plumage of the Lynford bird is actually more consistent with a 1st winter male Two-barred.

Uppertail coverts – one feature which may prove to be diagnostic in the identification of Two-barred Crossbill is the colour and pattern of the uppertail coverts. Svensson states “Other features to note which separate L.leucoptera from L.curvirostra are darker, blackish centres to the upperparts (esp. scap., mantle and longest upper TC…)…. and fine whitish tips to upper TC.” BWP also describes adult male Two-barred as having “black upper tail-coverts tipped pink-white”. In contrast, Common Crossbill appears to have greyer uppertail coverts, with rather diffuse paler fringes, either similar to the colour of the upperparts or rather dull buffy. The upper tail coverts also appear to me to be slightly longer in Two-barred Crossbill than Common Crossbill, perhaps corresponding to the longer tail overall of Two-barred. The Lynford bird appears consistent with Two-barred Crossbill in this regard – the uppertail coverts are distinctly blackish with comparatively broad, contrasting paler tips; some of the shorter feathers have rather reddish tips, but the longer feathers are tipped rather strikingly just off white.

So, while the plumage features of the controversial crossbill can perhaps be explained within the context of age and variable moult of Two-barred, there are two issues which still continue to cause consternation:

Congeners – the Lynford crossbill seems to associate most closely with a small group of Common Crossbills. Partly, this may have been forced upon it – over the winter, there were no other Two-barred Crossbills on site. However, in recent weeks, the Lynford bird has remained faithful to its small group, despite other Two-barreds being present. Indeed, on at least one occasion it has even been seen in the same tree as the other Two-barreds, and I have seen it in a neighbouring larch. If it is a Two-barred, why has it not decided to join other members of the same species?

Calls – the trumpet call of Two-barred Crossbill is generally deemed to be diagnostic. In addition, the flight call is slightly more clipped, even ‘clicky’ than Common’s ‘glip’, though the difference is subtle. As far as I am aware, the Lynford bird has not been conclusively heard to call. However, at no point has the distinctive ‘toot’ been heard from the group it hangs out with. In addition, we didn’t hear Two-barred flight calls from that group, despite listening hard. The other group of Two-barred has generally been very vocal. Even watching a lone juvenile in north Norfolk last summer, it would regularly ‘toot’, particularly on take-off or when coming in to land, despite no other members of the species being present. Could the Lynford bird just be a silent individual? I have struggled to tell whether any single birds seen previously in the UK have been silent, but it is interesting that many observers report never having heard the trumpet call in this country prior to this most recent invasion.

If the controversial Lynford crossbill isn’t a 1st winter Two-barred Crossbill, what are the alternatives?

Wing-barred Common Crossbill – these were historically considered to be a separate form, ‘rubrifasciata’ (Latin for red banded or barred). As the name suggests, these often have red or pink colour bleeding into the wing bar, which is not as well defined as in Two-barred. The wingbar of the controversial bird appears consistently to be pure white. The width of the wingbar in ‘rubrifasciata’ is “closely similar” to juvenile Two-barred, according to BWP. However, 1st year male Common Crossbill has “orange but rarely any pure red tones” to the body plumage “until the first complete moult”. So the reddish body plumage of the Lynford bird would be at odds with a 1st winter Common Crossbill. As well as this, the pattern of the uppertail coverts and the apparently moulted inner greater covert would not be consistent with that species either. This seems like the least likely explanation for the identity of the Lynford bird.

Hybrid Two-barred x Common Crossbill – this is perhaps the most convenient place to park the Lynford bird, as has undoubtedly been the case for other controversial individuals in the past. These difficult birds often seem to occur in invasion years, alongside other Two-barred Crossbills. However, though hybrids have been reported in captivity, there is no documented instance of hybridisation in the wild. If they do occur very rarely, what is the likelihood of one arriving with such a small invasion of Two-barreds? As discussed above, there is not necessarily any need to invoke the hybrid option to explain the plumage of the Lynford bird, which is consistent with a 1st winter Two-barred Crossbill after a more limited post-juvenile wing moult.

Conclusion

It would perhaps be too ambitious for me to state categorically that the Lynford bird is a 1st winter Two-barred Crossbill, but it does show a number of features which appear to point strongly towards that species. All the apparently anomalous plumage features can be explained in terms of age and moult. Certainly, it seems difficult to argue that it is just a wing-barred Common. It could perhaps be a hybrid, which might explain the lack of diagnostic vocalisations or its choice of flock, but would this be any more likely than a silent Two-barred? There is also nothing specific about it which points to a hybrid origin rather than a relatively retarded 1st winter Two-barred. Unless it actually calls, we may never know for sure. In the meantime, together with the other 1st winter Two-barred Crossbills at Lynford, it can potentially teach us a lot about the variation in post-juvenile moult and appearance of 1st year birds.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank James McCallum and Dick Filby in particular, for the interesting discussion about this bird before, during and after we saw it, and for their help in the preparation of this article. I would also like to thank all those photographers who very kindly allowed me to use their images.

Marcus Nash

April 2014

References

Cramp, S., (ed.), 1998. Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa.

Harrop, A.H.J., McGowan, R.Y. & Knox, A.J., 2007. Britain’s first Two-barred Crossbill. British Birds 100: 650-657.

Svensson, L., 1992. Identification Guide to European Passerines, 4th Edition.

van Duivendijk, N., 2010. Advanced Bird ID Guide.