Birding gear reviewed: (apps) - Warblr

It isn’t hard to imagine a future world where we don’t need to actually identify any of the birds we see or hear any more. That functionality could be built into our devices – how about a bird identification app embedded in a camera, for example? It feels like we may already have taken the first step down that slippery slope with the release of automatic bird song recognition smartphone apps.

Warblr is one such bird song recognition app, which claims to be able to recognise over 220 species of British bird. It was much hyped last year, as it sought to raise funds for development. Originally supposed to launch in time for spring 2015, it was delayed before finally launching earlier this month. But the most important question is, does it work?

The app itself is neatly laid and very simple to use, although it does have a rather annoying start up sequence. This is designed to show the user how to use the app, but it comes up each time it is started, not just the first time. It is possible to ‘skip’ the sequence by tapping on the bottom of the screen, but it would be much better if it went straight to the ‘Tap to record’ screen. Precious seconds could be lost and the subject could stop singing or even fly away in the meantime!

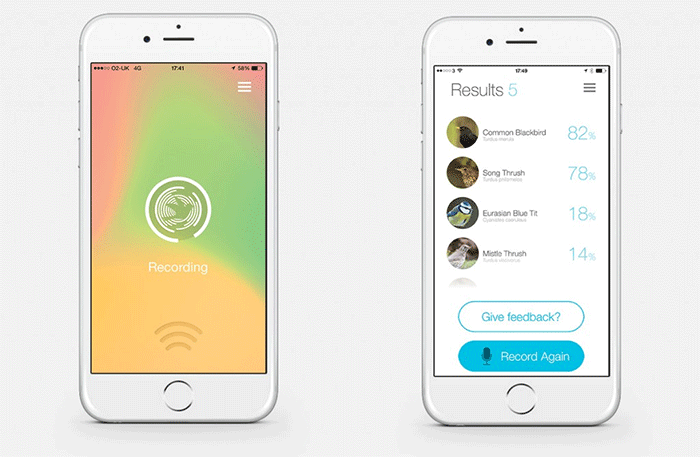

Tap the screen to start recording and turn the microphone towards the bird and the app does the rest. After 10 seconds the app looks to analyse the recorded clip. Unfortunately, this is where the first problem occurs. Unlike some other bird song recognition apps, Warblr requires an internet connection as the sound clips need to be uploaded and analysed by the developer’s online system. This requirement is not made clear anywhere until after you have bought the app and is an immediate disappointment.

The connection needs to be in the form of a 3G or 4G wireless or WiFi signal. While this is fine for many of the UK’s urban areas, in more rural parts we consider ourselves lucky to be able to find a 2G wireless signal. So this app is simply not going to work here, and these are often just the places, out in the countryside, where people might want to identify that strange bird they hear singing. Even worse, in practice using a WiFi connection the app was very unreliable, frequently returning a message that no internet connection was found, despite the fact that the device was perfectly capable of accessing webpages at the time.

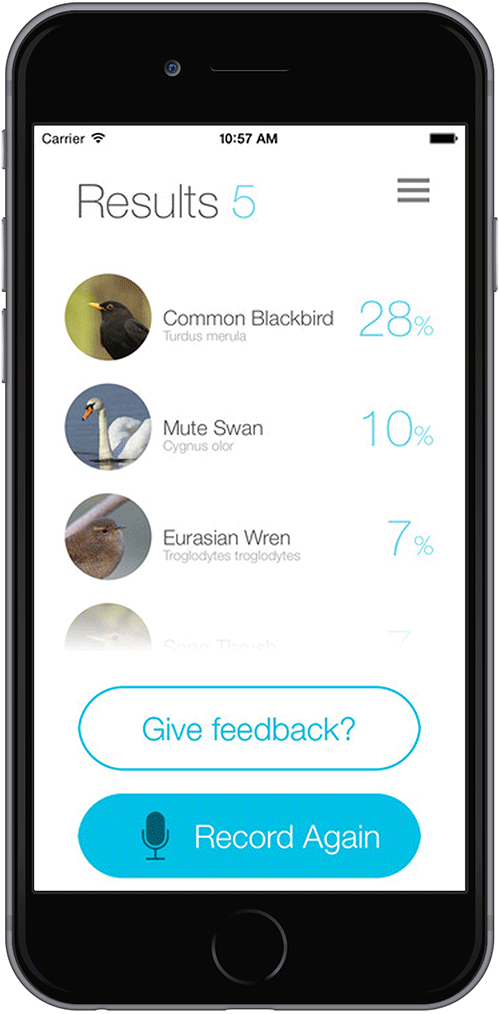

When it does manage to establish a network connection, the app takes around 20-30 seconds to analyse the sound clip and then returns a list of species which it thinks may be one the ones recorded. Warblr ranks the list with a percentage rating showing how likely it thinks each is to be the subject of the recording. The app’s FAQs suggest that ‘these judgements can never be 100% certain’, which is not entirely true. As humans, we can often be 100% certain which species we are listening to singing. It is just that the machine in this instance is not as good as a human brain in analysing bird song.

August is not the best time of the year to try out a bird song recognition app – there are not many birds singing at the moment. For that reason it may be a good time to launch one, to avoid the system becoming overloaded. However, setting Warblr against a series of high quality bird song recordings the results were distinctly disappointing. In a series of tests using songs of some of the commonest UK bird species, the app got the identification wrong more times than it got it right. In many instances, the correct species was not even on the list at all! In one instance a Chiffchaff was identified as a Tree Sparrow with 80% confidence (Chiffchaff was the second choice at 30%). Two different Robin recordings were identified as Blackcap and Chaffinch, respectively, for example. Rarely was the correct answer placed at the top of the list, or even in the top two which is the developer’s target.

Warblr claim to be able to achieve 95% scores in recognition in ‘optimum conditions’, but it may be that these conditions in the lab are just not indicative of the real world. Whilst it could be argued that the use of recordings is artificial, these have been generated with directional microphones and high quality recording equipment, which is also not how the bird song will be captured on a smartphone. Generally the device’s basic microphone will pick up a lot more background noise, including other birds singing, when used outside. It will be interesting to see how the app performs out in field conditions in the spring.

Tapping on a species on the list returned by the app brings up a screen with a photo and a little bit of text about it. There is a written description of the song, but it would be better if there was a pre-recorded sound clip of the species to listen to. The user could then compare this against the one submitted for analysis and see if the app might be right. In practice, many users may not know whether or not the clip of a Chiffchaff they submitted was a Tree Sparrow. This limits the usefulness of the app as a learning tool for people who would like to get to grips with bird song.

The developers claim that the main reason for not developing the app such that it could analyse sound recordings on the device is because one of their ‘key missions’ is to collect data on patterns of bird occurrence. This information is to be made publicly available to “zoologists and ecologists to monitor species growth and decline, patterns of migration, and ultimately to aid conservation”. Whilst this is a very laudable aim, there are numerous flaws in this argument, not least that the data will not be useful if the identification is inaccurate. In fact, the opposite is true. It will also be of little use to scientists if the data is skewed by the app’s ability to collect data only in built up areas where 3G or 4G wireless is available. It would arguably have been better to develop the app to analyse the sound recording on the device and then upload the resulting data if or when a connection was available. This would then have allowed users to actually use the app in rural areas as well.

Warblr is compatible with Apple iPhone, iPad and iPod touch, running iOS 7.0 or later.

It is available from the App Store priced at £3.99.

The developers are hoping to develop a version of the app for Android at some point in the future.

After all the hype, the reality is rather disappointing, if the truth be told. The need for a 3G/4G wireless or WiFi connection places major limitations on where and when the app can be used. The additional months in development time do not seem to have done anything to iron out the inaccuracies in the app’s analysis and all too often it still seems to return the wrong result. Unfortunately many users may not realise, given nothing to compare the bird they are hearing against.

The price is also over double the initially rumoured £1.99 and at £3.99 it is not a cheap app. This is a lot to pay for something that is little more than a gimmick and certainly not a reliable tool for identifying birds and learning birdsong, at least in its present state.

It may be that eventually bird song recognition develops to the point where it can deliver more accurate results. Or it may be that, like its big brother voice recognition, it consistently fails to deliver on the hype. In the meantime, we can perhaps sleep more easily knowing that the joy of birding is not about to be completely replaced by a series of apps.

Marcus Nash

03 September 2015

Download Warblr from the app store