Wintering grounds of Europe's Greater Spotted Eagles uncovered

One of Europe’s rarest birds of prey, the Greater Spotted Eagle, has been tracked by scientists to better understand its movements and the pressures it faces outside of the breeding season.

With fewer than a thousand breeding pairs in Europe and a tiny remnant population in the European Union, the Greater Spotted Eagle is listed as Critically Endangered. Although summer breeding territories of this charismatic, bog-loving raptor are well known in Europe, the wintering distribution of this migratory bird of prey is poorly understood, but has been thought likely to be restricted by suitable wetlands that provide sufficient food.

Prior to this study, published in Bird Conservation International, a number of wintering sites have been identified across the Mediterranean coast, but Greater Spotted Eagles have also been recorded in the Middle East and Northeast Africa. However, differences in wintering grounds between and within existing populations are little known, hampering efforts to conserve and identify threats to this species outside the breeding grounds.

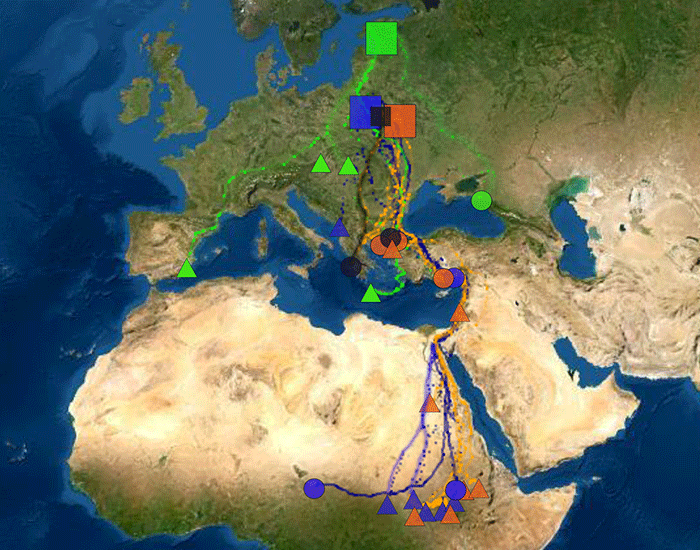

After fitting GPS tags to adult Greater Spotted Eagles breeding in Estonia, Poland and Belarus, scientists were able to analyse where these birds wintered. The results showed, for the first time, the extent of the wintering range and differences in wintering regions between the different breeding populations and between males and females.

Estonian birds all wintered across southern Europe, whereas Polish and Belarusian birds wintered in Southeast Europe, the Middle East or Africa. In Belarusian eagles, males were more likely to winter further south than females, with the majority of males wintering within a narrow belt in Eastern Sahel (South Sudan and Ethiopia) and females in coastal wetlands in Southeast Europe (southern Greece) and Turkey. This may also have been the case for Polish eagles, but there is uncertainty due to the small number of birds tracked.

Dr Adham Ashton-Butt, BTO author on the study, said, “The majority of the tracked eagles wintering in Europe were restricted to a small number of protected areas (SPAs or SCIs), highlighting the importance of these locations for this species. However, only two of twelve wintering sites in Africa have protected status, both situated in the same national park. The reliance on ecologically intact wetlands hints at one of the mechanisms of decline of this species, as the majority of wetlands in Southern Europe have been destroyed or degraded, with over 63% of Greece’s wetlands lost between 1950 and 1985”

This split between wintering grounds of females and males could have impacts on the conservation of the species. Most of the tracked females wintered at sites under formal protection, whereas males did not. This could lead to a sex-biased survival if African wetlands were degraded. In contrast, past habitat loss in Europe relative to Africa may have reduced numbers of females relative to males. Furthermore, protected areas can be insufficiently protected and eagles in some European protected areas are threatened by hunting or dangerous power lines. Ultimately, an imbalanced sex ratio could increase hybridization rates with Lesser Spotted Eagles (a more common, closely related species) and thereby increase the extinction risk for the Greater Spotted Eagle.

4 Dec 2021

Read the full paper for FREE: DOI: 10.1017/S0959270921000411

Share this story