UK’s largest breeding colony of Arctic Terns has vanished

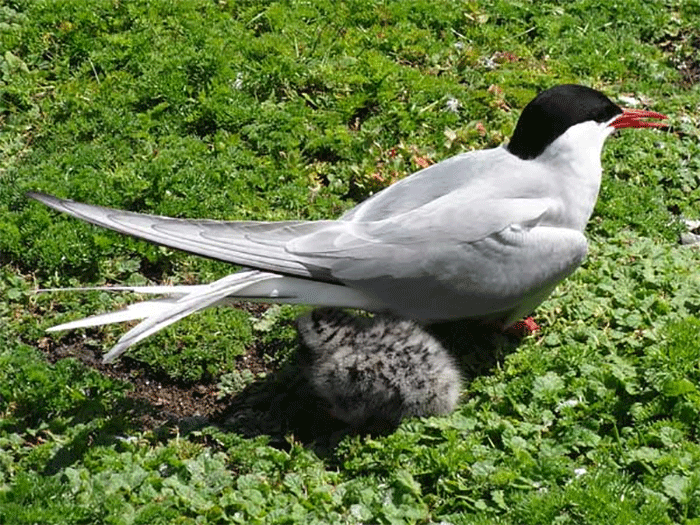

At this time of year, the tern colony on the Skerries, a group of rocky islets to the north of Anglesey, should be teeming with life, with adult birds noisily shuttling back and forth to sea to feed their growing chicks. This is the UK’s largest colony of Arctic Terns (home to 2,814 breeding pairs in 2019) – an elegant species known for their record-breaking pole to pole migrations from their northern breeding grounds to Antarctica, for the southern hemisphere summer. Arctic Terns experience more daylight than any other animal on Earth. Several hundred Common Terns also normally breed on the Skerries.

In 2020, this RSPB-managed seabird sanctuary has fallen silent. Because of the Covid-19 pandemic there are – for the first time in over a decade – no summer wardens living on the islands and, in the absence of this human presence, Peregrine Falcons have taken up residence. The RSPB believes that disturbance from the Peregrines is almost certainly the main cause of the desertion of the colony. The question is, where have the birds gone?

Scientists are hoping that watchful members of the public might be able to answer that question. Since 2013, a team of bird ringers licensed by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and supported by RSPB have been attaching individually coded leg flags to a number of terns each season. These leg flags, which are orange with a black code for Arctic Terns and yellow with a black code for Common Terns, can be read with binoculars or a telescope. People lucky enough to observe them can report their sightings and therefore help track the terns’ movements.

Dr Rachel Taylor, Senior Ecologist for BTO Cymru and one of the bird ringers in charge of the tern colour-marking project, said: “Terns are long-lived, and a single catastrophic year won’t be the end of the Skerries story. Historic tern colony collapses and recoveries like that of Shotton Steelworks in 2009 have taught conservation managers what’s needed to allow and encourage the colony to return to the Skerries in future. But a colony is made up of individuals, each making decisions for themselves: these colour-marked birds could give us a real insight into how those individual choices add together into ‘colony behaviour’. Where they go this year, and whether they survive to return and breed on the Skerries, are fascinating questions; the answers could help conservation managers keep the UK’s tern colonies resilient through future environmental change.”

Ian Sims, RSPB North Wales Wetlands Warden said: “It has been very saddening not to be able to give the Skerries colony the protection it needed this season, but what has happened only goes to emphasise the importance of the work that wardens do looking after this and other tern colonies up and down the country year after year.”

Please keep your eyes peeled and contact if any of these birds turn up on a beach near you!

22 June 2020

Share this story