The Proof Is in the Plumage: Birds Reveal Unexpected Exposure to Alcohol

A pioneering study shows that many bird species accumulate an alcohol by-product in their feathers, hinting at widespread and overlooked dietary exposure to ethanol

Detecting ethanol by testing feathers

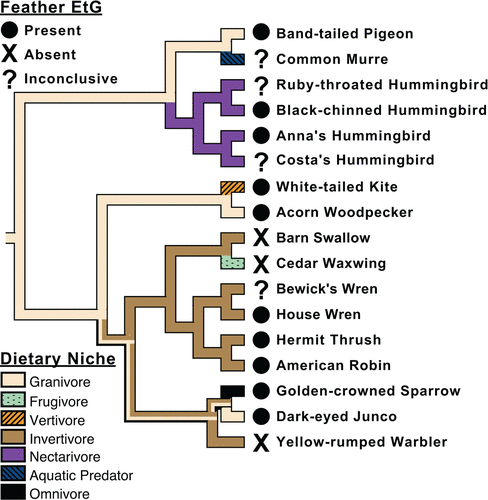

A new study published in Ecological and Evolutionary Physiology has unveiled a striking finding: many birds, across diverse diets and habitats, show signs of chronic ethanol exposure. Researchers adapted a technique from human forensic science to detect ethyl glucuronide (EtG) - a direct metabolite of ethanol - in bird feathers. Of 64 birds tested, 40 returned positive results, including all 14 Anna’s Hummingbirds sampled. The presence of EtG suggests that even wild birds may routinely consume fermenting nectar, fruit, or prey items containing ethanol.

Using samples from museum specimens, the team pulverised feathers and liver tissues and applied mass spectrometry to quantify EtG levels. EtG was detected in birds from a wide array of trophic niches - not just nectarivores like hummingbirds, but also granivores, invertivores, and even vertivores such as White-tailed Kites. While the hummingbird results confirm suspicions about sugar fermentation in artificial feeders, the broader distribution of EtG points to a more complex picture of alcohol exposure in wild birds.

Alcohol in nature: not just for mammals

Though previous research has documented alcohol exposure in mammals such as primates and treeshrews, this is the first study to robustly examine ethanol ingestion in birds using a biological marker. The researchers detected EtG not only in feathers but also in liver tissues, offering a more complete picture of exposure over time. Anna’s Hummingbirds, the best-sampled species, showed consistently high feather EtG levels - with 10 individuals exceeding 30 pg/mg, a threshold used in human toxicology to indicate chronic heavy drinking.

Yet other hummingbird species showed mixed or inconclusive results, and EtG was also absent from the only frugivore in the sample, a Cedar Waxwing. This variation may reflect differences in diet, molt timing, or even fermentation rates in food sources, which are influenced by temperature and microbial activity. The study authors caution that while positive EtG results confirm ethanol exposure, absence does not rule it out due to methodological and ecological complexities.

Not just nectar: a wider ethanol landscape

Perhaps most surprisingly, EtG was detected in species with no obvious link to sugary foods, including granivores like the Acorn Woodpecker, invertivores like the American Robin, and even predators like the White-tailed Kite. In some cases, the birds may consume fermenting fruit or sap opportunistically. In others, the ethanol may arise from endogenous fermentation in the digestive tracts of birds or their prey - an idea supported by findings of ethanol production in chickens and ptarmigan.

These unexpected detections broaden the ecological implications of dietary ethanol. Seasonal patterns of molt, varying access to fermenting foods, and migration could all influence EtG accumulation in feathers. The study opens the door to new research on how ethanol fits into avian nutritional ecology - and whether birds, like some primates, have evolved to tolerate or even exploit low-level alcohol exposure.

Feathers as forensic tools

Bird feathers, like human hair, are keratinised tissues that can retain chemical markers for long periods. The authors emphasise that feather-based EtG testing offers a non-invasive and retrospective window into birds' diets during the period of feather growth. However, they also note that factors such as feather structure, pigment, and wear may influence results. Refining the technique for avian use, and establishing species-specific baselines, will be key for future studies.

Although the EtG assay was originally developed for human hair, the successful detection of alcohol metabolites in feathers demonstrates its potential as a research tool. Liver assays, which reflect more recent exposure, proved less consistent, possibly due to faster metabolic turnover. Nevertheless, both tissues confirmed ethanol exposure in multiple individuals and species.

A new frontier in avian physiology

The findings challenge assumptions about the rarity of alcohol in bird diets and suggest that ethanol consumption may be a common, if largely invisible, part of avian life. With evidence of EtG in species from hummingbirds to robins, woodpeckers, and kites, the study raises new questions about the ecological, physiological, and evolutionary consequences of ethanol ingestion.

Further research could explore how ethanol affects avian behaviour and physiology, whether ethanol metabolism varies across species, and how often natural foods ferment to intoxicating levels. The researchers call for broader taxonomic sampling, seasonal diet studies, and experimental validation of ethanol metabolism in birds. As they write, “the proof is in the plumage” - and bird feathers may yet reveal much more about what birds eat and how they live.

June 2025

Share this story