Overdue and never again

Ross Ahmed delves into the BBRC stats and takes a look at some of the rarest birds many of which have not occurred for decades. Will British Birders get another chance to catch up with these sought after rarities? What will be the next blocker to fall?

Britain is well placed within Europe to receive a wide variety of vagrants from all directions of the compass. Despite this, some species have not been recorded in Britain for several decades with a few not recorded for more than 100 years. Some species unrecorded for decades have been seen by few current birders, leaving newer generations of birders longing for another chance to see the species in Britain. Species may not have occurred for a number of reasons such as the distance to their breeding grounds, physiology which does not allow vagrancy, range shifts and declining populations. Recent records of species that had not been seen for decades such as Tengmalm’s Owl, Steller's Eider and American Redstart gives rise to hope that more 'blockers' will be found soon.

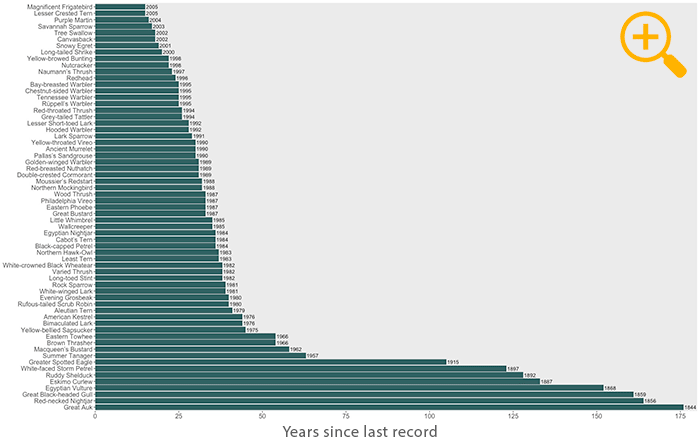

I downloaded the BBRC Statistics to 2018 spreadsheet. I ordered the species by year of last occurrence then filtered for Category A and Category B species for which there are no accepted records since 2005 or earlier. A total of around 63 species on the British list have not occurred in Britain since 2005 or earlier. Of these species, 8 have not occurred in over 100 years, 4 have not occurred in 50–99 years and 51 have not occurred in 15–49 years. The ranges of the 63 species primarily lie in North America or Asia.

The last accepted records of each of the eight species that reside in Category B of the British list were all over 100 years ago. Great Auk is now extinct and Eskimo Curlew is considered to be possibly extinct. The other six Category B species are still on the radar, although clearly, all are extreme vagrants. Great Black-headed Gull is on the British list on the basis of an adult that was shot at Exmouth, Devon in 1859. The species always feels just around the next corner for British twitchers, especially as the past 50 years has seen a breeding increase and westerly spread of the European population. But the reality is that Great Black-headed Gull remains an extreme rarity in northern and western Europe (Lawicki 2012). Similarly, White-faced Storm Petrel and Red-necked Nightjar are both on the British list on the basis of a single record over 100 years ago. The petrel was caught alive in Argyll in 1897 and the nightjar was shot in Northumberland in 1856. It seems perfectly possible that the petrel will be seen again in Britain, but the nightjar will take a combination of awareness, skill and serendipity to be found and identified. In contrast to the petrel and nightjar, Greater Spotted Eagle has been recorded on 13 occasions in Britain with the last in Herefordshire in 1915. But the chances of another eagle seem slim: it is a declining species and is classed as Vulnerable by the IUCN with a world population of just 3,300–8,800 individuals (IUCN 2020)

Four Category A species have not occurred in Britain for over 50 years and each have been seen on a single occasion only: Brown Thrasher (1966, Dorset), Eastern Towhee (1966, Devon), Macqueen’s Bustard (single modern day British record: 1962, Suffolk) and Summer Tanager (1957, Gwynedd). Chances of a reoccurrence of any of these species seems slim. There are no other Western Palearctic records of Brown Thrasher or Eastern Towhee, and the only other records of Summer Tanager were both on the Azores in 2006 and 2010 (Hobbs 2020). Furthermore, all four species are declining with Macqueen's Bustard listed as 'Vulnerable' on the IUCN Red List (IUCN 2020), while Brown Thrasher and Eastern Towhee are short-distance partial migrants (Billerman et al. 2020).

A number of vagrants may have gone unrecorded in Britain for so long due to the difficulty associated with their identification. Snowy Egret, Least Tern and Cabot's Tern would each be impressive finds in Britain given the difficulty in separation from their North American counterparts: Little Egret, Little Tern and Sandwich Tern. The only record of Snowy Egret in Britain was a bird that toured the west of Scotland in 2001–2002. Although Snowy Egret is readily separable from Little Egret, good views are required and it would be easy to dismiss a more distant bird as a Little Egret, particularly in areas where Little Egret is common. The sole British record of Least Tern in East Sussex, which returned to Rye Harbour NR each summer between 1984 to 1992, was initially detected by its squeaky call (Yates 2010). Least and Little Terns are difficult to separate on plumage and awareness of vocal differences between the two may be the best way of detecting future vagrants. Cabot's Tern is on the British list on the basis of a bird found dead in 1984 in Herefordshire that had been ringed near Beaufort, North Carolina, USA, on 25th June 1984. Cabot's and Sandwich Terns are difficult to separate, and although separation in the field is possible (Garner 2014), the detection of another Cabot's in Britain will require very alert observers.

A few species have occurred in large, one-off influxes in the past but have gone virtually unrecorded since. A famous influx of Nutcracker took place in Britain in autumn 1968 involving 315 birds (Hollyer 1970). Since 1968, just 22 Nutcracker have occurred with none since 1998 when a bird was in Kent in between 6th–7th September. There are over 500 records of Pallas's Sandgrouse in Britain but most of these occurred in large influxes in 1888–1889 (about 340 records) and 1863 (about 121 records). Since 1950 just 30 have occurred with the last in 1990 when a bird stayed on Shetland mainland for two weeks in spring 1990. Ruddy Shelduck is on Category B of the British list on the basis of a large influx in 1892 involving at least 61 birds. Despite being fairly frequent in Britain, it is not considered to have occurred in a wild state since 1892. It remains to be seen whether the influx of 14 Siberian Accentors to Britain in 2016 will also turn out to be a one-off event, leaving future generations of twitchers envious of those fortunate enough to witness it.

It has been a surprisingly long wait for some species. Nine individuals of Lesser Crested Tern are thought to have occurred in Britain since 1950 including a famous bird that returned to the Farne Islands, Northumberland each year between 1984–1997. And yet despite this sustained presence of the species in Britain, the last individual was as far back as 2005 (at various points along the Norfolk and Suffolk coast). Five Rüppell’s Warblers have been recorded in Britain including three in the 90s. But memories of the last individual, 25 years ago at Aberdaron in Gwynedd, are now rapidly fading. Given that Rüppell’s Warbler is long-distance migrant that breeds in the eastern Mediterranean, British birders might be forgiven for hoping for another before long. British birders are also patiently waiting for another showing of two other Western Palearctic breeders: Rufous-tailed Scrub Robin (five British records and last recorded 1980 in Devon) and Bimaculated Lark (three British records and last recorded 1976 on Fair Isle).

A number of species not recorded in Britain for decades breed relatively close to Britain at their closest point (Billerman et al. 2020). These species are generally sedentary or only short-distance/partial migrants, meaning that the chances of occurring in Britain are much lower than more migratory species. Hawk Owl breeds in Norway as close as 500km east of Shetland, which is the location of the only British record in 1983. Another highly desired species in Britain, Wallcreeper, breeds as close as 600km south of the Isle of Wight (therefore closer to the Isle of Wight than Aberdeen). Despite this, Wallcreeper was last recorded in Britain in 1985 on the Isle of Wight. Rock Sparrow has been recorded on a single occasion in Britain—in 1981 at Cley. At its closest point, Rock Sparrow it breeds a similar distance from Britain as Wallcreeper. Other continental species that breed relatively close to Britain include Lesser Short-toed Lark (only British record at Portland in 1992) and Egyptian Vulture (only British records in Essex in 1868 and Somerset in 1825).

In contrast to the species discussed in the previous paragraph, there several that have made it to Britain whose normal range is remarkably distant. Aleutian Tern has been seen on a single occasion and by a small number of observers in Britain: a bird graced the Farne Islands, Northumberland in 1979. Aleutian Tern is a Pacific species that breeds in eastern Siberia and North America. It has been 41 years since the Farnes bird but we could be waiting for a long time yet for another. Ancient Murrelet is another Pacific breeding species for which there is a single record in Britain. Unlike Aleutian Tern, the murrelet was available for the masses to see: an individual first seen on Lundy, Devon in 1990 returned to the island in both 1991 and 1992. The Lundy bird remains the only Western Palearctic record of Ancient Murrelet and along with Aleutian Tern is a contender for a species that may never been seen in Britain again.

Varied Thrush has occurred in Britain on a single occasion only in 1982 when a bird was present at Nanquidno, Cornwall for eight November days. Varied Thrush is distributed towards the Pacific coast of North America so its appearance is Britain is remarkable, although there is also a second Western Palearctic record in Iceland in 2004 (Hobbs 2020). Lark Sparrow, recorded twice in Britain, is another North American passerine whose range lies primarily in the western half of North America. The first was in 1981 at Landguard, Suffolk but the second was as long ago as 1991 at Waxham, Norfolk. There are no other Western Palearctic records (Hobbs 2020) so hopes for another in Britain seem optimistic. Two Asian passerines, Naumann's Thrush and Yellow-browed Bunting, were last recorded in Britain in 1997 and 1998 respectively. Both species are distributed relatively distantly to the east of Britain, however, there are several other Western Palearctic records of both species in recent years so another British bird seems imminently possible.

A whole host of North American landbird species not already mentioned have not made it to Britain for many years. The following species have not been recorded for 15 years or more (year of last record in parentheses): Purple Martin (2004), Savannah Sparrow (2003), Tree Swallow (2002), Tennessee Warbler (1995), Chestnut-sided Warbler (1995), Bay-breasted Warbler (1995), Hooded Warbler (1992), Yellow-throated Vireo (1990), Red-breasted Nuthatch (1989), Golden-winged Warbler (1989), Northern Mockingbird (1988), Wood Thrush (1987), Philadelphia Vireo (1987), Eastern Phoebe (1987), Evening Grosbeak (1980), American Kestrel (1976) and Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (1975). Each of these species are extreme rarities in Britain with 1–3 records each and very rare elsewhere in the Western Palearctic. Particularly for species such as Red-breasted Nuthatch, Eastern Phoebe, Golden-winged Warbler and Evening Grosbeak, which are weakly migratory or declining, we may be waiting some time for another.

While new species are added to the British list annually, there remains many species that have not occurred here for decades. These species have the potential to attract just as much interest as firsts for Britain. Thanks to the famous unpredictability of British birding, there is no way of telling which species will be next to fall. But there is little doubt British birders will get the opportunity to enjoy one or two of these species in the coming years.

Ross Ahmed

26 June 2020

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Andrew Harrop and Peter Allard

References:

Garner, M. 2014. Sandwich Tern and Cabot’s Tern. Challenge Series Autumn. Birding Frontiers.

Hobbs, J. 2020. A List of Nearctic Passerines Recorded in the Western Palearctic. Version 1.7.

Hollyer, J. N. 1970. The invasion of Nutcrackers in autumn 1968. British Birds 63: 353–378.

IUCN. 2020. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2020-1. https://www.iucnredlist.org.

Lawicki, L. 2012. Great Black-headed Gull: why is it still so rare in northern and western Europe? Birding World 25: 380–389.

Yates, B. 2010. Least Tern in East Sussex: new to Britain and the Western Palearctic. British Birds 103: 339–347.

Billerman, S. M., Keeney, B. K., Rodewald, P. G. and Schulenberg, T. S. (Editors). 2020. Birds of the World. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home

Share this story