Handbook of Western Palearctic Birds: Passerines

Hadoram Shirihai and Lars Svensson

The long awaited arrival of this handbook is sure to be the bird book publishing highlight of 2018. Twenty years in the making, it is finally here or, to be more precise, it is partly here. Published this year are two volumes, both covering passerines (volume 1: larks to warblers and volume 2: flycatchers to buntings). The non-passerine volumes will apparently follow in due course.

The handbook’s rationale is set out in the Introduction (reproduced in both volumes). Focusing on identification and taxonomy, it aims to be the most complete and profusely illustrated photographic guide to Western Palearctic birds. There is a particular emphasis on ageing and sexing and geographical variation whilst vocalisations and distribution are also addressed. Unlike ‘BWP’, however, there is no content on habitat, population, feeding, breeding biology, behaviour or movements.

The definition of the Western Palearctic follows political boundaries in pursuit of what is called a ‘birdwatcher-friendly’ approach. It therefore includes the whole of Iran and Arabia but correspondingly shrinks coverage in the Sahara by following the southern borders of Algeria, Libya and Egypt. Any species recorded at least ten times in the region by the end of 2016 is afforded full treatment, those with fewer records being listed in an Appendix.

The taxonomic approach followed here will doubtless attract some comment. The authors attempt to achieve what they call a ‘sensible balance’ between maintaining the status quo and adopting every new taxonomic development. Nevertheless, they go on to describe their taxonomic choices as ‘conservative and cautious rather than bold’ and the reader will quickly find that some of the taxa recently split by IOC (such as Stejneger’s Stonechat, Eastern Yellow Wagtail and Gran Canaria Blue Chaffinch) do not feature here as full species. Surprisngly in this context, therefore, the authors split Western and Eastern Subalpine Warblers. For a British reader, the most notable species-level difference is the treatment of Scottish Crossbill as the subspecies scotica of Common Crossbill.

The authors are of course both entitled and supremely qualified to make their own taxonomic judgments (and their rationales are clearly set out for all to read) but some may nevertheless find the lack of synergy with any of the global taxonomies a source of frustration. The differences are perhaps most evident in the treatment of subspecies. Here the authors adopt a particularly conservative approach, considering primarily morphological (rather than genetic) evidence and recognising around 15% fewer races than other checklists. This has led to something of a ‘bonfire of the subspecies’ and has had a particularly acute effect on Britain’s endemic taxa. As a result, fridariensis, hebridensis, zetlandicus and indigenus Wrens (but not hirtensis) are subsumed within borealis and the following indigenous forms are also deemed invalid - hibernicus Dipper, hebridium Dunnock, zetlandicus Starling, gengleri Chaffinch, britannica Goldfinch, autochthona Linnet, pileata Bullfinch and caliginosa Yellowhammer. It will be interesting to see whether the publication of this handbook has any influence on the keepers of the IOC World Bird List, on which of course the British List is now predicated.

The Introduction also covers the handbook’s approach to taxonomic sequence, nomenclature and English names, an overview of the species accounts, a glossary, a selected gazetteer, a brief guide to moult and ageing in the field and a list of general references. Then come the detailed species texts. These follow a standard format which covers the species’ names, a brief introduction, identification, vocalisations, similar species, ageing and sexing, biometrics, geographical variation and range, taxonomic notes and references.

The texts are both detailed and authoritative, drawing on the authors’ vast knowledge and experience, targeted fieldwork in all corners of the region and extensive museum research in all its major bird collections, the latter focused particularly on biometrics and subspecies definition. The content on such troublesome groups as small larks, grey shrikes, Yellow and White Wagtails, wheatears, stonechats, Acrocephalus warblers and redpolls is therefore as comprehensive and up to date as you can get, with all the taxonomic uncertainties explained in detail. Also included are range maps for each species, happily reproduced at a decent size and showing, for each subspecies, breeding and/or winter ranges and, where applicable, approximate migration routes.

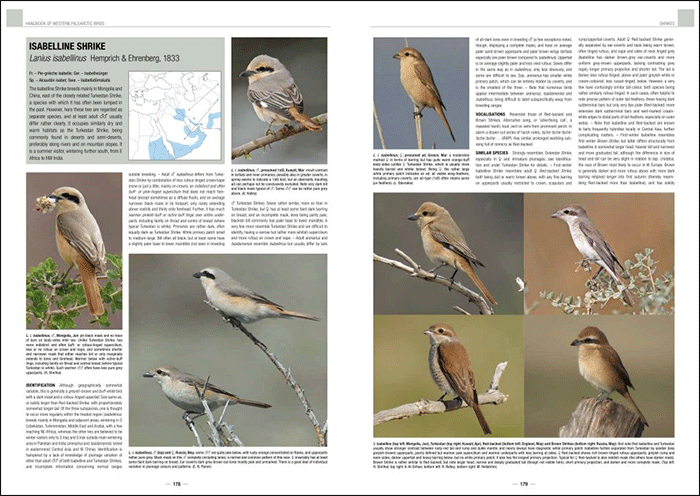

The photographs are, however, what catches the eye. This project has always been about creating a photographic handbook and the authors have benefited hugely from the recent improvements in digital camera technology and the resultant proliferation of high quality images. The handbook therefore showcases a splendid array of high quality photographs, aiming to cover all significant plumages. Each species typically has around ten images but there are no fewer than 49 of Yellow Wagtail! Included are some rarely photographed taxa such as leucocephala Yellow Wagtail and some, until recently, little known species such as Basalt Wheatear. This collection therefore represents a huge achievement, both by the 750 contributing photographers and also by the authors and members of the editorial team who have tracked them down.

The photographs are accompanied by long captions which draw attention to salient features, summarise some of the points raised in the detailed text and, most importantly, include a location and date. These are hugely helpful although I did find one or two errors. For example, the image of a very dull and pale first-winter female Red-throated Thrush captioned as taken in England was in fact photographed in Arunachal Pradesh, India. Similarly, the Wilson’s Warbler image captioned as ‘England’ is of a bird in Scotland (on the Outer Hebrides in 2015). The image of a female Pine Bunting, also described as taken in England, is of another Scottish bird (on Shetland in 2016) but, more importantly, it features an individual which had yellow primary fringes and which has therefore been accepted as a Pine Bunting x Yellowhammer hybrid. Conversely, the image captioned ‘either Yellowhammer or hybrid Pine Bunting x Yellowhammer’ depicts an accepted Pine Bunting (in Northumberland in 1990). Finally, two of the captions to images of nominate ater Coal Tit refer to a non-existent subspecies ‘cristatus’.

Such nitpicking aside, this is a magnificent and impressive piece of work and also a sumptuous and attractive product. Until now, the two essential passerine references have been ‘BWP’ and the Svensson ringers’ guide. The former, however, suffers from somewhat impenetrable text and sparse illustrations of variable quality whilst the latter is necessarily succinct and aimed at ‘in the hand’ identification. This new handbook solves all these problems, offering detailed and accessible text designed for field identification and supplemented by the best images available.

This is now the definitive passerine guide for the Western Palearctic region. It might appear expensive but it comprises two very substantial (and heavy) volumes and as such represents great value for money. Let’s hope that the non-passerine volumes are not too far away.

Andy Stoddart

24 July 2018

Share this Review

Commission for Conservation

Rare Bird Alert does not profit from the sale of books through Wildsounds. Instead we are part of their Commission for Conservation programme where a percentage of every sale made through RBA helps supports BirdLife's Spoon-billed Sandpiper Fund.