Flamingos create water tornados to trap their prey

New research reveals flamingos as active hunters using vortex-generating beaks and feet to trap their prey

Flamingos as dynamic predators

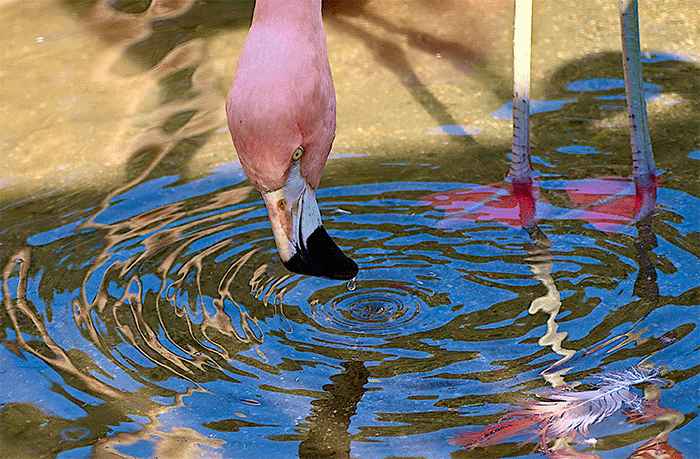

Long thought of as graceful, passive filter-feeders, flamingos are now revealed to be far more dynamic in their foraging. A new study combining live animal observations, mechanical modelling, and fluid dynamics has shown that Chilean Flamingos (Phoenicopterus chilensis) actively manipulate water flow to create vortices that trap their planktonic prey. Rather than relying solely on their comb-like lamellae and upside-down feeding posture, flamingos use a suite of specialised movements involving their head, beak and feet to stir up prey and funnel it directly into their mouths.

This research, led by Victor M. Ortega-Jimenez and colleagues, marks a major shift in our understanding of flamingo feeding behaviour. Their L-shaped beak, S-curved neck and morphing feet all play active roles in creating vortical traps that lift prey from sediment and concentrate it in optimal feeding zones. The birds’ characteristic stomping, head-retracting and beak-chattering behaviours each serve a distinct hydrodynamic function.

Generating feeding currents with head and beak

Flamingos produce tornado-like vortices when rapidly retracting their heads (~40 cm/s) from the bottom of shallow waters. These spiralling flows stir up sediment and lift brine shrimp towards the surface. Their uniquely bent beak, particularly the flattened upper mandible, helps enhance this effect, operating like a suction plate during upward head movement.

Further experimentation with a 3D-printed flamingo beak confirmed the fluid dynamic forces at play. These head-induced vortices were powerful enough to trap live brine shrimp and sediment particles, funnelling them upwards for easier access at the feeding interface.

Asymmetric beak chattering creates unidirectional flow

Using high-speed cameras and a mechanical beak model, researchers found that the chattering of a flamingo’s mandibles - up to 12 times per second - creates a strong, directional flow. This flow draws particles and prey directly toward the beak, significantly improving capture efficiency. When live brine shrimp were introduced, they were swiftly carried toward the mouth opening, unable to escape the current.

Mechanical simulations showed that this chattering increased prey capture rates by approximately sevenfold. The unique motion of the upper mandible alone - oscillating while the lower one remains fixed - appears to generate the suction-like flow observed in live birds.

Morphing feet stir the substrate

Flamingos are often seen stamping their feet in shallow lagoons, a behaviour previously thought to disturb sediment. The study now shows that these foot movements generate horizontal vortices. As the webbed feet spread and fold with each stomp, they create eddies strong enough to lift prey like copepods, mayfly larvae, and brine shrimp from the substrate and trap them in front of the beak.

Using a bioinspired mechanical foot, researchers replicated this stomping behaviour and confirmed its effectiveness in entrapping small aquatic organisms. Flow speeds generated by the morphing foot were far greater than the swimming capabilities of the prey, ensuring capture within the vortex zone.

Surface feeding and vortex streets

When skimming the water surface, flamingos position their beaks downstream - opposite to most filter-feeding vertebrates. A 3D-printed model of the flamingo’s head placed in a flow tank revealed the formation of a Kármán vortex street, a series of alternating vortices that create a recirculation zone directly behind the head. Live prey and brine shrimp eggs were trapped in this zone, enabling surface feeding.

The L-shape of the flamingo’s beak again proved essential. It allowed the beak tip to sit precisely within the flow’s collecting region, aligning it with the main current to funnel food particles directly into the mouth. This unusual feeding orientation is made possible only by the bird’s unique beak curvature and head posture.

Evolution and broader implications

The findings raise questions about the evolution of the flamingo’s bent beak. Juvenile flamingos have straighter bills and rely on parental crop milk, which may indicate a developmental trajectory toward vortex-based feeding. Fossil evidence also supports a progression from straight to curved bills among ancient flamingo lineages.

The study’s implications extend beyond avian biology. Engineers could draw on these insights to design more efficient particle collection systems, such as those used in water purification or filtration technologies. Nature’s elegant fluid engineers may soon inspire industrial innovations.

20 May 2025

Share this story