Finders-in-the-Field: Black-and-white Warbler on Inishbofin, County Galway

I like the roar and rattle of wind and rain on a dark night. Snug beside a fire in a cottage on an Irish island, enjoyment of the elements is tinged with guilt when you hope that, outdoors, a howling west wind might entrain American birds and slingshot them across the North Atlantic. October 2019 was barely one day old when the Irish meteorological office went into panic mode. Its warnings were heeded by the government and the Atlantic seaboard braced itself for the remains of Hurricane Lorenzo.

I was not on Inishbofin. I was on another island – Inishturk, County Mayo. I went there to test out a different hunting ground but now it was time to leave. I faced a dilemma, however. The projected storm might prevent me getting out to Inishbofin or, if I got there, the island could take a hit. The eye of Lorenzo had County Galway in its sights. I decided to head back home to Northern Ireland and wait. Listening to weather reports, nothing much came of the fuss. A few ferries were cancelled and Inishbofin was lashed but only with rain. Apart from wondering what birds might have arrived, I had another pressing reason to get out to Inishbofin – I was to lead a bird-watching tour starting on Sunday 6th October. For reconnoitring purposes, I like to arrive at least two days in advance of a tour group. I lost the first day due to no ferry sailing and now, on Saturday 5th October, rain was constant. That was not the worst. As seems to happen more and more in the windy west, salt-laden gales had not so much stripped foliage from trees and hedges but flayed the vegetation to withered shreds. Lorenzo had turned green sylvan oases of alder, sycamore and birch into lifeless brown toothpicks, bereft of insects. Some of my favourite patches of cover looked like burnt toast.

With Angelus bells clanging on the radio at noon, the final shower passed and the wind dropped. It felt like a miracle. To save time, I decided to ignore all shorebird habitat and blitz gardens and bushy habitats, reckoning that the sudden calm would enable me to find arrivals. I had to prioritise. I headed first to a standing crop that, in late September, held a Melodious Warbler and a Common Rosefinch. The farmer had kindly agreed not to cut the crop until after the bird tour. I needed to know if he had been good to his word. He had. The place was still buzzing but the mob consisted of nothing more than Linnets and House Sparrows. I felt like I had wasted an hour. I switched tactics. Under normal circumstances I walk everywhere. Instead, I flagged the first passing car and got a lift to my next hotspot. Hotspots on Inishbofin only become hotspots when they attract a rare bird. When that happens, they acquire a reputation that never tarnishes and henceforth such places are always looked at in the belief that lightning will strike twice. And, because the range of habitats is limited, another rara avis quite often is added to the roll of rarities for a tiny garden.

The afternoon wore on. I was finding nothing. Inishbofin is not a cakewalk and off-piste effort is obligatory. Wellingtons are compulsory, dint of ploughing through boggy terrain to reach off-road habitats. Disappointment met me at every turn: frazzled vegetation and no migrants. At least I was travelling light, so I was not cursing the extra handicap of a rucksack on my back. This was a whiz-around; a pre-tour reconnaissance. By late afternoon I reached the northeast-facing side of the island. Surveying the network of fields below me I was thrilled to see that Lorenzo had not desiccated foliage in this area. Five willow thickets nestled among reeds had been spared. I knew each thicket by name – named after the first unusual bird I had found there. I squelched through cattle-poached swamp and approached. ‘Pishing’ is essential to test what lies within. Sometimes, if I have time, I just sit silent, overlook the habitat – and wait. That is often effective. However, warblers are likely to keep safe and hidden, especially when they can feed unobtrusively. So I gave the first pair of thickets a thorough ‘pish’ from close quarters. Things started to look up. The first held a Goldcrest; the second a Willow Warbler. Believe it or not, such minute rewards are significant; an omen that the next bird might be a Yellow-browed Warbler or a Lesser Whitethroat. Either of those would be Irish quality and make a fitting reward on a bird tour.

The final three thickets were farther off. Once I reached them, I still had more places to check. I knew I wasn’t going to finish the itinerary. But because of a favourable overnight weather forecast – clear skies and almost calm – I could resume in the morning. The biggest thicket was the most inaccessible. In previous years I used to beat my own way to it through a reed-bed. These days a couple who own the land have embarked on a kind of The Good Life enterprise and established vegetable plots, planted alders on the edge of the willows and excavated a small pond for a pair of aggressive farmyard geese. I no longer have to hack a path to reach the thicket. Into the bargain, what used to be a trickling waterway running through the spot has been widened and commandeered by the geese. They didn’t like it when I shoo-ed them away.

The gander was still hissing at me when I crossed the small stream and sat on a ground-level bough within the thicket. Its interior was almost cathedral-like. Lichen covered thicker boughs like tree tattoo and moss carpeted the ground. I could only see part way into deeper recesses. Everywhere was overhung by greenery. Normally I would wait, watch and listen. Not today. Time was tight. Psssh, psssh, psssh. I heard a clipped, monosyllabic call which was repeated. In a moment of brain freeze I wondered if the owners had added something else to the menagerie. What was making the sound? I peered ahead and right away picked up a shifting, fidgety silhouette. Pssh, pssh, pssh. The bird kept coming, as though magnetically attracted. My brain didn’t register the call or the incoming sprite, still slinking around tangled boughs and heading in my direction. With a quick raise of binoculars, I would be able to see enough of it to put a name to the inquisitor – a Wren, a Goldcrest, maybe a small warbler?

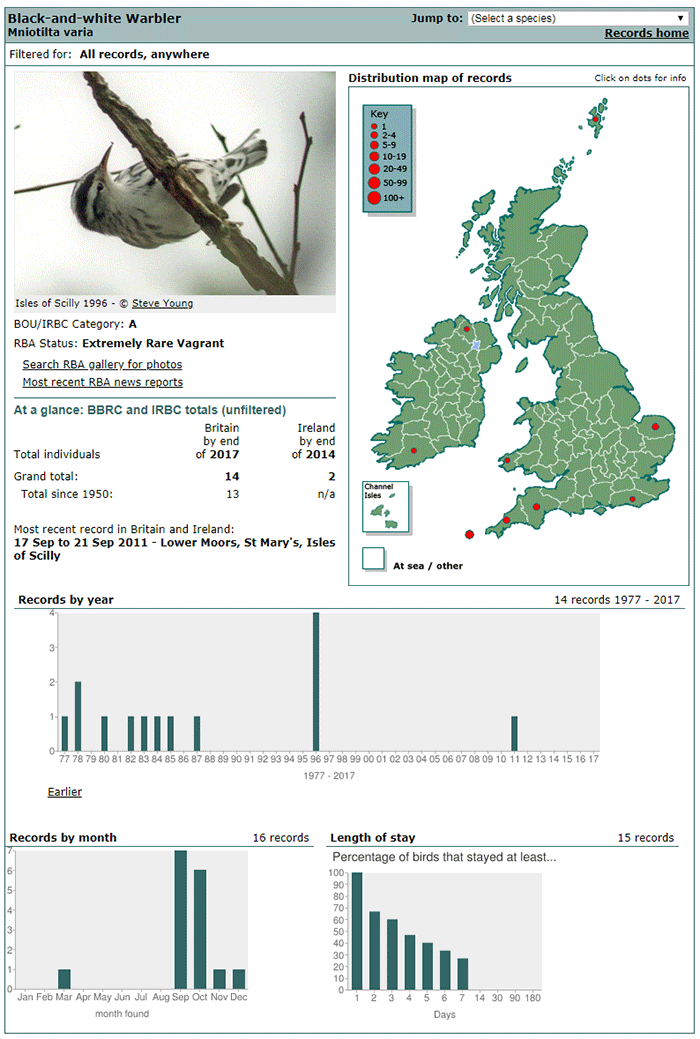

Identifying the bird could not have been easier. In fact, my speed of attaching a species name to the moving target was accomplished in a millisecond. Black-and-white Warbler is one of the most distinctive birds on the planet. And I know them like the back of my hand. Just two autumns ago I was in Newfoundland, Canada, on a mission to photograph Blackpoll Warblers for a chapter in To the Ends of the Earth – my book about migration. Always among the first wave of nosy-parkers coming to pishing was numerous Black-and-white Warblers. Why I even got some pleasing photographs of them. But this was different. This was the greatest Black-and-white Warbler that ever hatched since time began. Bizarrely, I had seen the species before in Ireland. In 1984 one was found in, of all places, the middle of Northern Ireland. That was my first and Ireland’s second. So I knew that Ireland’s third – the bird flitting around in front of me – had taken 35 years to materialise. Not that I care about documenting a rarity for a bird records committee but I started to feel like a man who had had his right arm amputated. I had, deliberately to save weight, left the camera behind.

How times have changed. Of about eight people who saw the Black-and-white Warbler in 1984, nobody had a camera. Lack of one did not detract from our enjoyment. But now I started to kick myself. Stupid I know, especially as the only person I am in competition with is myself. I tried to put the thought out of my mind. I backed out of the bird’s refuge and broke the news to The Good Life couple. I said that I expected it would still be there in the morning and that I too would be back at dawn. I was. I hardly slept a wink. I wanted some pixels to commemorate it. A small living thing had opened a drawer and placed a dream in it. A picture would make it real forever. The weather forecast was accurate. It was a beautiful morning after a starry night. I watched the willow leaves warm in the morning sun. Then a movement. Just a Willow Warbler. Damn. But a new migrant nonetheless. A second bird stirred, disturbing foliage that allowed me to follow its progress until – Holy Smoke! – the head of a Barred Warbler emerged. Another rarity. But not the one I wanted. Game over.

Anthony Mcgeehan

14 October 2019

Previous Records

Share this story