Breaking the Binary: Same-Sex Partnerships in Birds Are Widespread and Undervalued

New review challenges assumptions about avian behaviour, revealing the ecological and evolutionary roles of same-sex pairings in birds

Long Overlooked, Now In Focus

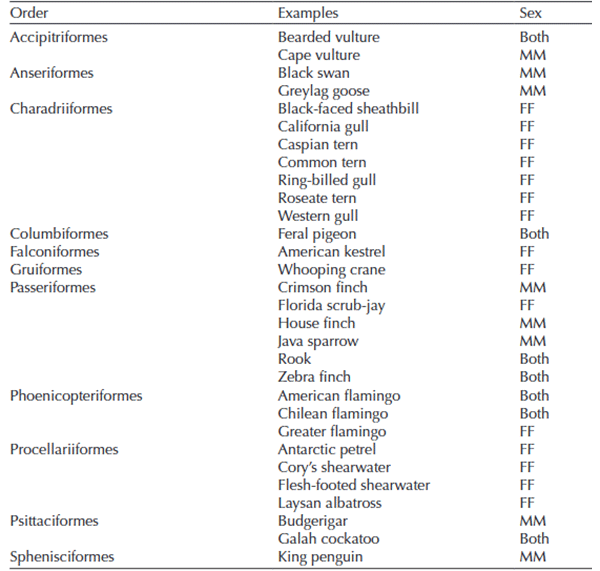

Same-sex sexual behaviour in animals has long puzzled scientists and stirred controversy, but a new review of current research highlights just how widespread, persistent, and potentially adaptive such behaviours are in birds. Published in the Journal of Avian Biology, the paper synthesises evidence from across the avian world, challenging assumptions that same-sex partnerships are rare mistakes or anomalies. Instead, it paints a nuanced picture of social bonds that often offer tangible reproductive or survival benefits - even when no direct offspring are produced.

Same-sex pairings in birds include all the hallmarks of heterosexual bonds: courtship, nest-building, cooperative parenting, and sometimes lifelong fidelity. Yet despite this, they are still often dismissed as biologically irrelevant or misinterpreted as the result of mistaken identity. According to the review, this is not only scientifically unfounded but also a missed opportunity to better understand the diverse behavioural strategies birds use to survive and reproduce.

Partnerships Beyond Reproduction

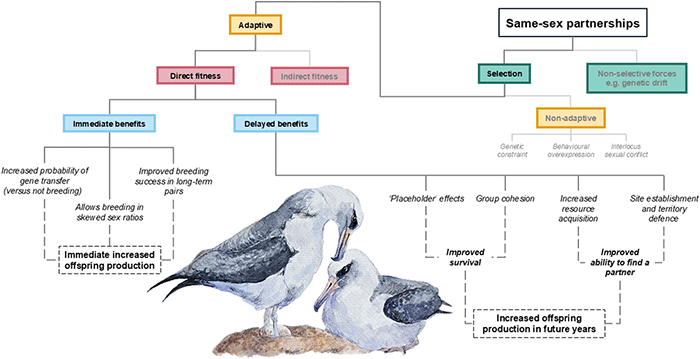

While reproduction is a central concern in evolutionary biology, Gillies and Siddiqi-Davies argue that not all pair bonds need result in offspring to be biologically significant. Same-sex partnerships can bring immediate and delayed fitness benefits: from successful egg incubation and chick rearing in female-female pairs, to joint territory defence and improved social standing in male-male pairs.

Among the clearest examples are the female-female pairs of Laysan Albatrosses, which can form stable, long-term bonds and raise chicks with fledging rates comparable to male-female pairs. Similarly, in King Penguins, up to 24% of pairings at a studied colony were male-male, despite low reproductive output - a figure that cannot be explained by sex ratio imbalances alone.

Adaptive or Byproduct? A Complex Evolutionary Question

Historically, same-sex sexual behaviour has often been categorised as maladaptive or a byproduct of social constraints. Yet the evidence suggests many such partnerships are the result of active mate choice and long-term investment. In Black Swans, for instance, male pairs may form temporary trios with a female just long enough to obtain eggs before excluding her and raising the offspring together.

Female-female pairs also demonstrate strategic coordination: in some tern and shearwater species, females manage incubation shifts and resource allocation in ways that mimic, and sometimes outperform, heterosexual pairs. The potential for direct or indirect fitness gains from these partnerships demands a reevaluation of traditional evolutionary models, especially those grounded in rigid sex-role assumptions.

Why We’re Missing So Much

The authors point to both historical bias and methodological challenges as reasons why same-sex partnerships have been under-reported. In many species, especially those that are sexually monomorphic, only genetic testing can reliably reveal the sexes of bonded pairs. Even in dimorphic species, confirming the nature and longevity of partnerships requires intensive, long-term monitoring - something few studies are equipped to do.

Biases in interpretation have also played a role. Early reports often assumed such pairings resulted from errors or captivity-related stress. Terms like “prison effect” reveal more about human cultural assumptions than animal behaviour. As Gillies and Siddiqi-Davies note, removing anthropocentric and heteronormative filters is critical to fully understanding the breadth of avian social systems.

Where Next for Research?

The review concludes with a call to action. With only 30 peer-reviewed studies documenting same-sex pair bonds in birds, the field remains wide open. The authors encourage more rigorous data collection - including long-term nest monitoring, genetic sampling, and cross-species comparisons. They also propose a framework for evaluating both adaptive and non-adaptive explanations, including the role of pair duration, resource access, and social cohesion.

As evolutionary biologists expand their focus to include behavioural diversity across all types of partnerships, same-sex bonds in birds stand as an important and underappreciated part of the story. Understanding them more fully may unlock new insights into the flexibility, resilience, and complexity of avian social life.

23 May 2025

Share this story