Ancient Humans Feasted on Great Bustards During Burial Rituals

New evidence from a Moroccan cave shows ancient humans shared ritual meals of Great Bustards while burying their dead

Bird bones and burial grounds

Recent excavations in northern Morocco’s Taforalt Cave have revealed that Great Bustards were not only hunted for food but played a ritual role in some of the earliest known human burial practices in Africa. Archaeologists found the butchered remains of these large birds intermingled with human burials dating back around 15,000 years - the clearest sign yet that these birds featured in ceremonial feasts to honour the dead.

The study, conducted by an international team including researchers from the Natural History Museum in London, underscores the complex relationship between early humans and their environment. Taforalt, also known as Grotte des Pigeons, is already known as the oldest cemetery in Africa, but the latest findings show that the site was more than just a resting place for the dead - it was also the scene of highly symbolic social gatherings.

Great Bustards in the Late Stone Age

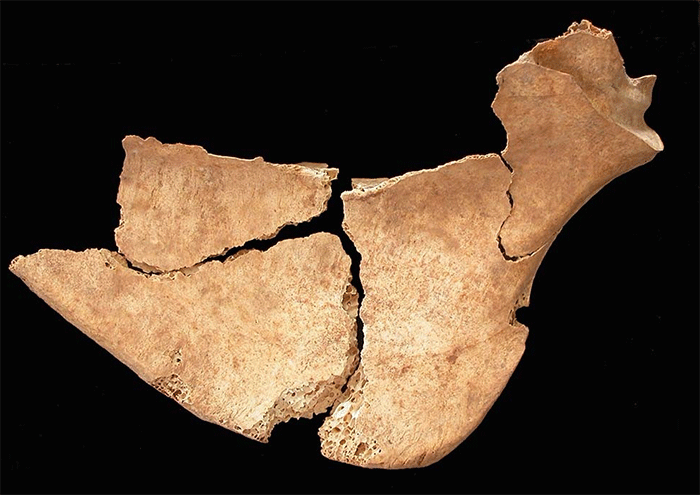

The Great Bustard (Otis tarda), one of the world’s heaviest flying birds, would have been a striking and challenging quarry. Yet its remains have now been confirmed as part of the archaeological assemblage at Taforalt - with bones showing clear cut marks indicative of deliberate butchery. According to Dr Joanne Cooper, a NHM ornithologist and co-author of the study, “It looks like they were being brought into the cave to be eaten during these funerary rituals.”

The evidence suggests the birds were hunted locally, and their selection may not have been merely opportunistic. As the team points out, the effort required to capture and prepare such large and wary birds would likely have made their inclusion in the funerary context especially meaningful.

Food, memory, and meaning

Far from being a simple protein source, these birds appear to have held symbolic significance. The researchers suggest that their consumption may have played a role in bonding the community, reinforcing memory and shared identity through the act of feasting. While the full ritual logic remains speculative, the findings add to a growing body of evidence showing how food and animals were incorporated into spiritual life in early human societies.

“This wasn’t everyday subsistence hunting,” said Professor Louise Humphrey, another lead researcher. “This was food with a meaning - something to mark a moment of importance.”

Ancient connections and modern conservation

The Great Bustard has long vanished from North Africa, but a small relict population of around 70 individuals still survives in Morocco today. Once widespread across the continent, the bird is now globally threatened, with populations in steep decline across much of its Eurasian range due to habitat loss and disturbance.

The new findings add a cultural and historical dimension to modern conservation efforts. That these birds were once revered and featured in early human rites may offer an additional reason to protect the dwindling remnants of their range today. “We’ve long known that these birds are part of our natural heritage,” Dr Cooper noted. “Now we see they are part of our human heritage too.”

May 2025

Share this story